"Blind Elephant: A Stitched Body in the Dark" Exhibition Review

31 Jan 2026The Basement as Epistemology, the Other as Structure

A basement is already an argument. Before any artwork is encountered, it proposes a position about what is kept below: what is stored, what is protected, what is hidden, and what must be endured. It is an architecture that carries memory without declaring it, a space that resists neutrality not through curatorial rhetoric but through its very position in relation to the ground above. Dastan Basement has long carried this charge in its name alone, refusing the self-mythology of the white cube and the promise of transparency that so often accompanies gallery space.

"Blind Elephant" (14–28 November 2025), curated by Saam Keshmiri, did not attempt to correct or soften this condition. Nor did it aestheticize the basement into a stylized environment. Instead, it worked from within the basement’s existing logic, amplifying it until darkness itself operated as the exhibition’s primary medium. Darkness structured how bodies moved, how works appeared and disappeared, and how meaning was assembled through partial encounter rather than total visibility. The exhibition brought together works by Akvan, Sadra Bani Asadi, Ali Bakhtiari, Pouya Parsamagham, Kasra Paashaaie, Peybak, Newsha Tavakolian, Mohammad Hossein Khatamifar, Khalzan, Shooki, Nima DW, Shayan Sajadian, Hamid Shams, Mehdi Shiri, Bita Fayyazi, Alborz Kazemi, Mahsa Merci, Milad Mousavi, and Farrokh Mahdavi.

Curated in the immediate aftermath of the twelve-day war, "Blind Elephant" emerged from a moment of collective disorientation marked by infrastructural failure, power and water outages, the absence of functioning shelters in a city still shaped by the memory of a previous war, and a population experiencing events largely through screens rather than direct encounter. Yet the exhibition did not represent war as image or subject. There were no scenes of destruction offered for contemplation, no attempt to translate violence into spectacle. Instead, it staged the perceptual and social conditions that war produces: fragmentation, partial knowledge, sensory distortion, and enforced proximity.

The title invoked the parable of the elephant in the dark, in which individuals grasp different parts of a single body, each convinced of their own truth, none able to comprehend the whole. In "Blind Elephant", this parable was not mobilized as a lesson in humility or epistemological caution. It functioned instead as a lived structure. Partial sight was not framed as a philosophical failure but as a shared condition intensified by crisis and mediated by contemporary technologies of visibility. The exhibition did not ask to be interpreted from a distance. It asked to be entered, navigated, and endured.

From the outset, "Blind Elephant" positioned otherness not as a theme to be represented, but as a structural condition distributed across artists, works, audiences, and modes of attention. Each element arrived from a different margin, disciplinary, social, infrastructural, or perceptual, and the exhibition did not attempt to reconcile these differences into a coherent whole. Instead, it assembled them into a provisional body, stitched together through proximity and friction. Like Frankenstein’s creature, the exhibition existed as a composite being: uneven, excessive, and alive, defined less by harmony than by the fact that its disparate parts were forced to function together.

Seeing Under Surveillance

The encounter with the exhibition began before the artworks themselves. At the threshold, visitors were confronted with a monitor displaying live security-camera footage of the basement interior. This ordering was deliberate. One was seen before becoming a viewer, observed before observing. The gaze was continuous, anonymous, and unreciprocated. The camera did not dramatize surveillance through an Orwellian spectacle or threat, but appeared banal, almost administrative, echoing the visual infrastructures that increasingly shape everyday life, where being seen no longer requires an identifiable observer. Only after this encounter did visitors pass through a heavy black curtain and enter the main space, a descent into near-total darkness in which the familiar cues of gallery behavior were abruptly withdrawn.

Inside, windows were sealed and marked with taped crosses reminiscent of wartime impact precautions, columns were wrapped with blankets, and the space was stripped of ambient light. These gestures were not symbolic insertions for effect, but felt carried over from another context, as if the basement had been temporarily reassigned as a shelter rather than an exhibition space. Vision, here, was not assumed. To see anything at all required the activation of a flashlight, most often the phone’s built-in torch, a gesture that immediately made looking a deliberate act. Light was no longer evenly distributed or passively received. It was directed, finite, and selective. To illuminate one surface was to leave another in darkness, and every act of seeing carried with it an act of exclusion.

This simple shift reconfigured spectatorship at a fundamental level. The darkness dismantled the familiar etiquette of gallery-going almost immediately. There was no prescribed route through the space, no stable sequence in which works announced themselves, no hierarchy of attention established by lighting or placement. Visitors wandered, paused, collided, whispered, retreated. Bodies became obstacles rather than neutral presences. Sound and smell accumulated unpredictably, and the space no longer encouraged contemplation from a distance but demanded navigation. This reconfiguration of spectatorship echoed a broader contemporary condition. In a world saturated with images, visibility has become both currency and trap. Social media trains us to believe that what is not seen does not exist, while simultaneously overwhelming us with partial, curated, and algorithmically selected fragments. "Blind Elephant" translated this condition into space. Here, visibility was labor, not entitlement. And being seen was unavoidable.

What emerged was less fear than a sense of estrangement, with the architecture, the artworks, and even other visitors remaining familiar while no longer behaving as expected. This estrangement aligned closely with Freud’s notion of the uncanny, not as something unfamiliar appearing, but as the familiar returning in distorted form. The basement was known, yet it refused to behave as a gallery should, and in this refusal, it articulated one of the exhibition’s central propositions: that we inhabit structures we recognize without fully understanding how they operate.

Cohabitation and Disturbance

Within this environment, the exhibition unfolded less as a sequence of separate works than as a shared spatial condition produced through proximity. The works were not connected by formal coherence or a unified aesthetic, but by the fact that they occupied the same confined space, where separation was never complete. Each work retained its own internal logic, yet none could be encountered in isolation. Sound, shadow, odor, and bodily movement travelled across the basement, ensuring that the experience of any one work was continually shaped by the presence of others.

As the exhibition progressed, these overlaps became more pronounced. Sound carried between installations, smells accumulated in the sealed space, particularly those produced by organic materials, and the atmosphere itself began to register these interactions. The basement did not function as a neutral backdrop against which works were individually perceived. Instead, it imposed a shared sensory field that bound them together without resolving their differences. What emerged was not unity, but a condition in which fragmentation was held together through enforced coexistence.

This closeness recalled the conditions of wartime sheltering, where bodies are brought together out of necessity rather than choice. Individuality is compressed, personal boundaries erode, and coexistence becomes a matter of endurance. Blind Elephant drew on this logic without romanticizing it. Cohabitation was not presented as an ethical ideal or a space of mutual understanding, but as a condition marked by friction, negotiation, and the unavoidable awareness that one presence reshapes the experience of another.

This dynamic was articulated with particular precision in a sculptural work by Kasra Paashaaie, which remained silent until illuminated. Light activated sound, and the longer illumination persisted, the more the sound degraded, shifting from intelligible speech into noise. What unfolded was not an exchange of information but a chain of effects. To look was to intervene, and because sound radiated outward, one viewer’s decision immediately reshaped the experience of others nearby. Looking did not remain a contained or private act. As sound moved through the space, a single viewer’s engagement extended beyond their own encounter, subtly altering what others heard and felt around them. Individual attention became inseparable from its effects within the shared space.

The work resonated strongly with the logic of contemporary media culture. Today, drawing attention to something is often understood as a moral act, yet the repeated circulation of images and stories frequently flattens meaning rather than clarifying it. Personal testimony slips into generic content, and increased visibility can strip events of their specificity instead of revealing it. Kasra’s work did not explain or criticize this condition from a distance; it recreated it within the exhibition itself, placing viewers inside a situation where acts of illumination carried immediate consequences for others, and where attention could not be exercised without reshaping the shared environment.

Sound continued to operate as a connective tissue throughout the basement, leaking between works and refusing containment. Alongside it, smell emerged as an unplanned but welcomed element, particularly in relation to a tattooed cowhide by Khalzan. Tattooing inscribes memory, affiliation, and experience directly onto skin, and when transferred onto animal hide it became unsettling in its insistence on surface as record. Detached from a living body, the hide remained densely marked with imagery drawn from subcultural and gang iconography, layered without explanation or narrative anchor. They resisted translation, presenting themselves as marks of encounter rather than symbols to be decoded. Psychoanalytic notions of abjection help illuminate the discomfort this produced. Detached skin sits uncomfortably between life and object, disturbing familiar categories and unsettling the viewer’s sense of orientation. Khalzan’s work holds onto this instability, presenting the body not as a subject to be understood but as evidence, a surface that carries lived experience without explaining it. Nearby, Bita Fayyazi’s cockroaches appeared not as metaphors of disgust but as companions, figures persistently othered in cultural imagination yet remarkable for their capacity to survive catastrophe. Their presence aligned them with those pushed to the margins during conflict, creatures that endure when systems collapse.

Fragment, Body, Evidence

Fragmentation was not merely thematic in "Blind Elephant"; it was structural. Nowhere was this more evident than in the installation by Ali Bakhtiari, which functioned as the exhibition’s conceptual anchor. Composed of a grid of transparent pouches, each carefully labeled and containing personal remnants, hair, underwear, photographs, fragments of film, the work resembled an evidence table assembled with forensic precision. The materials suggested intimacy, even vulnerability, yet withheld narrative context. They invited the viewer to speculate, to connect, to reconstruct, while offering no possibility of confirmation. What was presented was not a story, but the remains of one.

Bakhtiari’s installation operated less as an object to be decoded than as a method for thinking through uncertainty. The pouches did not resolve into a coherent image or chronology; instead, they insisted on fragmentation as a condition of knowledge. Each element appeared meaningful, yet none could stand in for the whole. The viewer was compelled to assemble narratives from residue alone, only to confront the instability of those constructions. In this sense, the work staged interpretation itself as a fragile and speculative act.

This logic resonated strongly with the exhibition’s broader engagement with partial sight and mediated perception. Like the experience of war filtered through screens, rumors, and incomplete information, Bakhtiari’s work offered fragments that circulated without grounding. Truth appeared not as something revealed, but as something imagined, assembled provisionally, then unsettled. The installation thus enacted Roland Barthes’s notion of the “death of the author” not as a theoretical proposition, but as an embodied experience. Authorship receded, narrative authority collapsed, and meaning shifted decisively toward the viewer, who was left to negotiate significance without guidance or resolution. The inclusion of film fragments intensified this condition. Operating like montage without instruction, they suggested sequences without determining order, movement without direction. Each viewer effectively edited a private version of the work, producing a narrative that could never be verified against an original.

If "Blind Elephant" functioned as a stitched organism assembled from disparate parts, Bakhtiari’s installation operated as its nervous system, registering disturbance, transmitting uncertainty, and refusing closure. The work echoed both wartime rumor and the algorithmic logic of social media feeds, where fragments circulate faster than verification and accumulation is mistaken for knowledge. The personal was transformed into evidence; intimacy became data. Familiar materials, fabric, hair, images, were rendered uncanny through their isolation and repetition, stripped of the narratives that once stabilized them.

In this sense, Bakhtiari’s work did not simply reflect the exhibition’s concerns; it condensed them. It articulated, with particular clarity, the condition "Blind Elephant" sought to inhabit: a world in which meaning is pieced together from fragments, authority is dispersed, and certainty remains perpetually out of reach.

Performance, Audience, Exposure

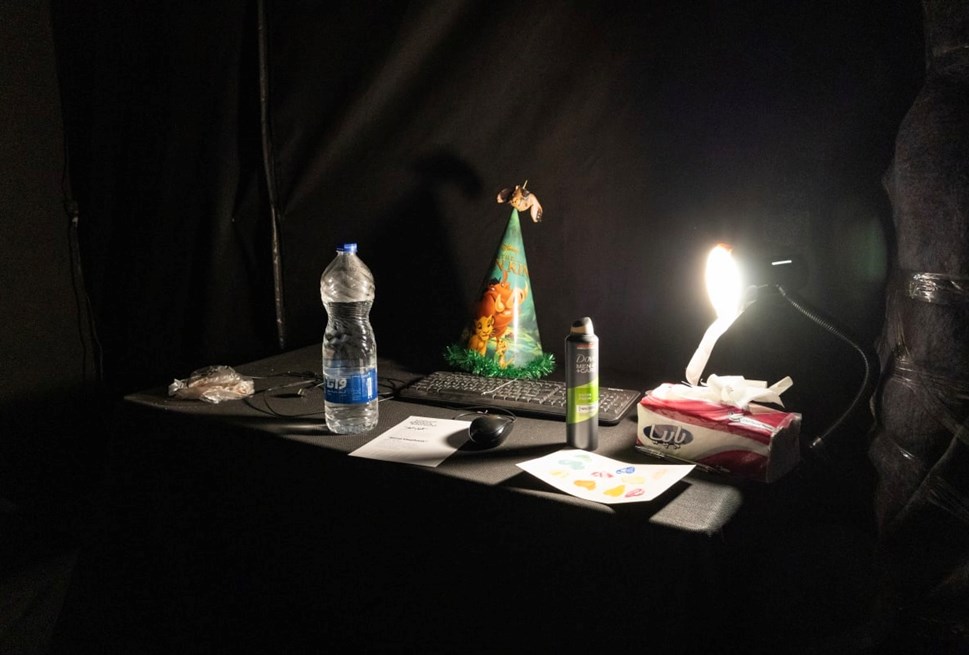

This speculative condition extended into the exhibition’s engagement with performance, most forcefully through the sustained inhabitation of the basement by Nima DW. Living in the space for several days—sleeping, livestreaming, and remaining continuously visible, Nima collapsed distinctions between artwork, artist, and exhibition. His living conditions were deliberately reduced to bare essentials: a narrow bed, a military blanket, plastic chairs, basic monitors. Comfort and aesthetic distance were stripped away.

What fundamentally destabilized the exhibition, however, was not only Nima’s presence, but the audience he brought with him. His followers, many of whom came from music, livestream, and online subcultures rather than contemporary art, entered Dastan Basement carrying different expectations and habits of attention. During the opening, these publics collided. Regular gallery visitors found themselves sharing the space with viewers accustomed to continuous presence, unedited duration, and direct address.

This encounter was not seamless. It was marked by friction. Different rhythms of looking, different thresholds of patience, different assumptions about authorship and access occupied the same room. Nima’s audience followed him continuously, watching him sleep, wait, speak, and remain idle. The exhibition was never fully offline Nima’s practice did not comment on social media from the outside. It inhabited it fully, acknowledging the economies of attention, validation, and surveillance that structure contemporary expression. Performance here was not theatrical but existential. Visibility was not chosen; it was endured.

Surveillance haunted the exhibition from beginning to end. Cameras watched silently, peepholes concealed small video works visible only to those willing to search, and visitors were never certain whether their actions were private or recorded. The gaze was anonymous and asymmetrical, echoing both classical models of surveillance and contemporary digital conditions. Someone was always watching, yet no one could be identified. This uncertainty mirrored the conditions under which contemporary subjectivity is formed: always visible, rarely understood.

The Other, The Monster, the Whole

In this sense, "Blind Elephant" aligned itself with long traditions of horror and "camp" that have consistently returned to the figure of the other. These traditions are not primarily concerned with fear or shock, but with exposur, with making visible the social boundaries that determine who belongs and who does not. Horror has often done this by assembling bodies that fail to conform, while camp has used excess, humor, and exaggeration to survive exclusion without erasing it. In both cases, the “monster” is less a fantasy figure than a social one.

The exhibition followed this logic closely. Like Frankenstein’s creature, assembled from incompatible parts and never allowed to settle into a stable identity, "Blind Elephant" existed as a stitched body. Its coherence did not come from harmony or agreement, but from the fact that its parts were forced into proximity. The exhibition held together not because its elements fit, but because they continued to function alongside one another despite their differences. The monster here was not an aberration introduced for effect; it was structural. It emerged from exclusion itself and remained legible through persistence rather than resolution.

This logic extended across the exhibition’s artists, works, and audiences. Each occupied a position that resisted easy assimilation Artistic practices did not align neatly with dominant art-world expectations, materials resisted easy interpretation, and different modes of attention collided rather than merging. Rather than smoothing over these differences, the exhibition allowed them to remain visible. Otherness was not something represented at a distance, but something enacted through the exhibition’s very structure.

Within this framework, “queer” functioned not as a sexual identity but as a position. To be queer, here, was to be othered: to exist outside the norms that regulate visibility, value, and legibility. It described the condition of those who do not fit established categories, the socially displaced, the economically precarious, the culturally illegible, and the practices that remain marginal to institutional comfort. "Blind Elephant" did not attempt to redeem or normalize these positions. It chose instead to inhabit them, allowing discomfort and imbalance to remain part of the experience.

The exhibition’s embrace of excess, unease, and dark humor should be understood in this light. These were not stylistic gestures, but ways of staying present within conditions that resist clarity. Like camp, which turns marginality into performance without denying its violence, Blind Elephant allowed its works to move between vulnerability and defiance, seriousness and absurdity. The grotesque appeared not as spectacle, but as a mode of persistence.

By staging itself as a stitched body composed of othered parts, "Blind Elephant" refused the comfort of mastery. It did not offer the viewer a stable position from which to understand the whole. Instead, it asked for proximity without resolution and attention without certainty. In doing so, it framed the figure of the monster not as something to be feared or corrected, but as a way of thinking through contemporary conditions of exclusion, mediation, and survival.

Conclusion: Seeing Without Mastery

Ultimately, "Blind Elephant" refused resolution. It did not offer a message to be agreed with or a conclusion to be carried home. Instead, it staged a condition of partial sight, shared space, and unavoidable proximity. Visitors left having seen different exhibitions, assembled different narratives, and encountered different bodies. In doing so, the exhibition challenged the solitude of the islands we inhabit, our feeds, our comfort zones, our ideological enclosures, and asked what might happen if these islands were forced into contact. The answer was not reassuring, but it was necessary.

By embracing darkness not as spectacle but as method, "Blind Elephant" transformed Dastan Basement into a site where perception itself was at stake. In a moment shaped by war, mediation, and uncertainty, the exhibition did not promise clarity. It offered something more difficult and more honest: the experience of not knowing, together.

- Cover and Slider Image: dastan.gallery