"Disconnect to Connect: Contemporary Fiber Art" Exhibition Review

07 Dec 2025"Disconnect to Connect: Contemporary Fiber Art", curated by Shahed Saffari and presented at Liikeh Art Factory in Kashan, brings contemporary Iranian fiber practices into direct conversation with a site whose history is inseparable from the medium itself. Housed in a former textile factory, one that still contains and operates an original weaving machine, the exhibition stages a narrative about material continuity, labor, and transformation. Rather than simply gathering artists who work in fiber, Disconnect to Connect situates textile within the layered histories of gendered labor, industrial production, conceptual experimentation, and the evolving place of material practice in Iranian contemporary art. The result is an exhibition that is not only about fiber, but about how fiber thinks: how it holds memory, structures space, and reveals the political and aesthetic conditions in which it is made.

The Factory as Site of Meaning

Liikeh’s significance is not metaphorical, it is material. Located in the industrial zone of Kashan, a city historically synonymous with textile production, the space retains its industrial identity. The presence of a functioning textile machine is not a romantic relic but an active reminder of the labor that once animated the building. Its rhythmic sound and mechanical presence create spatial tension. The viewer encounters contemporary artworks in fiber while the factory continues, in some small capacity, to perform its original function.

Within this environment, textile is stripped of nostalgia. Instead, it is encountered as a medium shaped by histories of labor and economies of scale, by gendered divisions of work, and by the shift from artisanal intimacy to industrial production. The building’s architectural memory, its scale, light, and rough surfaces, stands in deliberate contrast to the delicacy, density, or conceptual abstraction of the artworks. This contrast reinforces the exhibition’s central idea, that fiber is not only a medium but a site where questions of continuity, rupture, and authorship are negotiated.

Bita Fayyazi | Beautiful Creatures (Wrapping in the Roots of the Spruce) | 2014 | Yarn weaving, recycled yarn, discarded objects, broken ceramics, metal wire, and tree bark | 360 × 20 × 22 cm

Curatorial Vision: Reweaving Traditions of Labor and Thought

Saffari’s curatorial framework takes the medium of fiber not as a theme to be illustrated but as a point of entry into larger questions about the politics of making and the infrastructures of art in Iran. The exhibition title carries her curatorial argument: “disconnect” points to rupture, that is, the dislocation of textile from its historical contexts, from communal labor, or from recognition within institutional art history. While “connect” suggests the act of rethreading these severed relations through contemporary artistic practice. This movement between rupture and reconnection becomes the conceptual engine of the show. Saffari is not interested in presenting fiber art as a category; instead, she uses it to ask how materials carry memory, how labor is valued or obscured, and how certain forms of making have been marginalized despite their deep cultural and technical significance.

Rather than grouping works by style or generation, Saffari’s selection emphasizes the range of what fiber can do in contemporary Iranian art. The artists approach textile through stitching, weaving, layering, sculpting, assemblage, and conceptual abstraction. Some remain closely attuned to inherited techniques, drawing upon the structures of carpets, embroidery, or tribal weaving, while others use fiber to push into sculptural or architectural territory. This plurality reflects not only the flexibility of the medium but also the diversity of artistic positions in Iran today, where the cultural weight of textile intersects with contemporary concerns around identity, labor, and material experimentation. What unites these practices is an insistence that textile is neither ornamental nor secondary, but a mode of thinking. Fiber is an embodied, process-driven medium capable of holding ideas as robustly as any traditional art form.

By placing these works within a factory, a site defined by production, repetition, and labor, Saffari dissolves the usual distinctions between art and craft, between concept and process. The former logic of the building, especially its industrial past, and its collective labor, resonate with and complicate the works on display. In this context, fiber is allowed to speak from the position of its own history, as a material shaped by domestic and industrial labor, by gendered economies, and by the shifting status of craft within Iran’s art world. This interplay between medium and site enables the exhibition to move beyond aesthetic presentation into a deeper reflection on how artistic practices respond to and sometimes resist the material conditions that surround them.

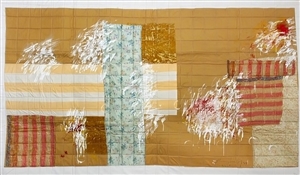

Afsaneh Modiramani | The Colors of the Sunset Wrote the Poetry of the Summer Evening | 2015 | handwoven and embroidered fabric with hemp, synthetic fibers, cord, wire, wool, and cotton | 220 × 180 cm

Artists and Material Approaches

Although the exhibition brings together a wide group of artists, certain shared concerns help clarify the conceptual and material range of their practices. One key thread is the way many artists negotiate between inherited techniques and contemporary reinterpretation. Farhad Ahrarnia, Taher Asad-Bakhtiari, and Nargess Hashemi each work with the deep technical lineage of fiber, but they redirect its forms toward new ends. Ahrarnia uses embroidery to interrupt the image, shifting it from ornament to a conceptual gesture. Asad-Bakhtiari draws on tribal weaving codes only to distill them into minimalist compositions that question authenticity, replication, and the underlying logic of the loom. Hashemi turns to the textures of domestic interiors, using embroidery to show how memory persists in the material surfaces of everyday life. In their practices, fiber becomes a carrier of technical knowledge and social memory, revealing the continued relevance of fiber within contemporary artistic discourse.

Other artists approach fiber as a language of embodiment and psychological terrain. Hoda Zarbaf, Bita Fayyazi, Shadi Parand, and Shirin Mellat-Gohar use fabric and thread to articulate forms of intimacy, emotion, and gendered experience. Zarbaf’s assemblages, composed from worn fabrics and personal remnants, evoke a sense of exhaustion and vulnerability, proposing emotional landscapes that resist linear narrative. Fayyazi’s material experiments push textile toward sculptural form, complicating the assumed softness or domesticity of fabric. Parand’s layered surfaces build identity through process and repetition, registering the gradual accumulation of gesture. Mellat-Gohar foregrounds touch and texture as modes of self-representation, allowing fiber to communicate states of feeling rather than depict them. Through these approaches, textile becomes a means of exploring the body, interiority, and the porous boundaries between self and material.

A further set of artists translates the structural logic of textile into spatial and architectural investigations. Fereydoun Ave, Homa Delvaray, Negar Farajiani, and Laleh Memar Ardestani each treat fiber as a system of construction rather than a surface for decoration. Ave’s layered compositions manipulate texture and collage to create spatial tension, while Delvaray transforms graphic precision into patterned rhythm that echoes architectural order. Farajiani blurs ornament and structure, drawing attention to how textile logic can be used to build or destabilize space. Memar Ardestani extends fiber into geometric abstraction, working with modularity and repetition as principles derived from the loom. Their works demonstrate that textile is not only a material but a structural vocabulary capable of organizing form, rhythm, and spatial perception.

Finally, artists such as Zahra Imani, Fariba Boroufar, and Afsaneh Modirmani foreground process, duration, and the material resistance of fiber itself. Imani’s minimal interventions highlight fragility and the potential for collapse, while Boroufar’s serial gestures evoke repetition as a meditative act. Modirmani’s weaving and unweaving introduce cycles of making and undoing, treating textile as a temporal phenomenon rather than a fixed object. In these works, fiber becomes procedural: a record of time and labor unfolding through material.

Taken together, these practices reveal the elasticity of textile as an artistic language. Across the exhibition, fiber holds memory, constructs space, embodies emotion, and resists fixed categorization, demonstrating its capacity to move fluidly between tradition and experimentation, concept and form.

Panel One: Medium, Market, and Material Challenges

The exhibition’s first panel discussion, featuring curator Shahed Saffari, Dastan Gallery founder Hormoz Hematian, and curator Ashkan Zahraei, extended the exhibition’s concerns by situating fiber within broader artistic and institutional contexts. Saffari opened by describing how her curatorial process began with artists she already knew closely, particularly those working with Dastan. This familiarity, she explained, shaped her early decisions, reflecting how personal networks and shared material languages often guide the formation of an exhibition.

Hematian offered a complementary view from within the gallery system. Although Dastan has long supported artists working with textile, he noted that fiber remains relatively underrepresented in the Iranian art scene. Part of this, he explained, stems from practical challenges: many fiber-based works, such as those by Homa Delvaray, require complex planning and technical coordination to install. But he also pointed to broader economic factors. In a fragile market shaped by inflation and financial uncertainty, collectors tend to gravitate toward conventional media like painting, which they perceive as more stable investments. This dynamic, he suggested, has less to do with artistic merit and more to do with the pressures placed on artists and galleries by economic conditions. His remarks underscored a central tension within the medium’s reception in Iran: despite its conceptual richness and sensory immediacy, fiber often circulates within a market that has not yet fully adapted to it.

Panel Two: Rethinking the Category of “Art”

In the second panel, Zahraei spoke alone on the book The Invention of Art and posed a central question: what counts as art? Using objects such as Chiwara masks, a 15th-century embroidered hood, a painted lockbox, and a 16th-century salt shaker, he argued that the boundary between function and art has never been fixed. Many objects produced for daily life now reside in museums because of their aesthetic and cultural significance.

This argument resonates strongly with Disconnect to Connect, where textiles, long relegated to domestic or utilitarian roles, are repositioned as sites of artistic inquiry. Zahraei’s discussion underscored the exhibition’s broader stakes, that is, the reevaluation of material hierarchies and the recognition that fiber has always carried aesthetic, social, and epistemological weight, even when it was not categorized as “art.”

Conclusion: Fiber as a Continuum of Labor and Reflection

Disconnect to Connect succeeds because it treats textile not as a theme but as a framework for thinking. By situating contemporary fiber practices within a former factory, the exhibition reanimates the relationship between material and site, labor and expression. It acknowledges the gendered and domestic histories of textile while advocating for its conceptual significance in Iranian contemporary art.

Through Saffari’s curation, the works gain meaning not only from their materiality but from their placement within a building shaped by production, repetition, and industrial memory. The panels further deepen this perspective, highlighting how fiber operates across markets, institutions, and histories of classification.

Ultimately, the exhibition argues that fiber art is not an alternative to contemporary art but an integral part of its evolution. It is a medium that continues to weave together tradition and innovation, intimacy and structure, the past labor of the factory and the present labor of thought.