From the Patterns of Golestan Palace Tiles to the Bare Lives of Passive Bodies

30 Aug 2022Original text in Farsi by Nafiseh Saleh Abadi

Translated to English by Omid Armat

From May 20 to June 6, 2022, Navahi Projects, located on Fereshteh avenue, Tehran, hosted an exhibition of works entitled "Golestan" by Ahmad Morshedloo.

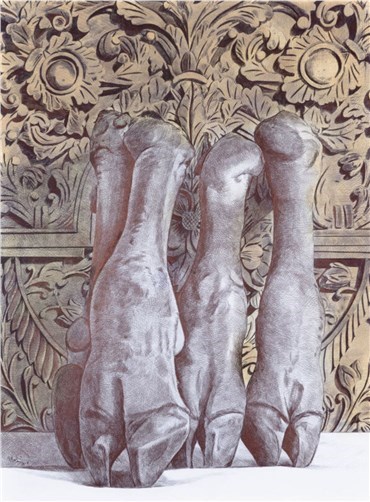

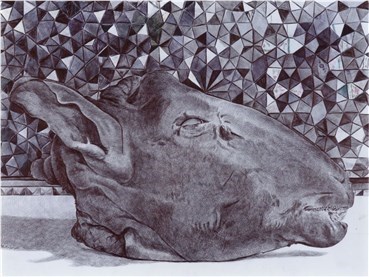

There is a huge, unignorable image of a severed head of a sheep on a simple green background placed inside a glass frame right at the entrance of the show's interior space. The head's color texture and half-open mouth and eyes have added to the realism presented before the viewer's eyes. More than terrifying, the head is a beautiful object due to its size, position, and framing. Entering the exhibition room, we see another big image showing a sheep's feet positioned side by side, all leaning against a pale wall right behind the previous frame showing the head. On the wall on the left side, the viewer faces Morshedloo's similar yet distinguished human subjects. These are naked bodies that, according to the exhibition's statement, "there is nothing left of them but a bare life and alive yet lifeless faces whose bodies are not controlled by any force."

Ahmad Morshedloo | Untitled | 2019 | pen on cardboard | 120 × 90

Ahmad Morshedloo (b. 1973, Mashhad) is a contemporary Iranian painter renowned as a Realist artist because of his frequent depictions of the human body. So far, Morshedloo is mainly known by the visual arts audience for his social concerns and his tendency to express them in his works. He attended the Fine Art School in 1980, and after going through some years that, according to the artist, formed a period of confusion for him, he started his education in painting. Receiving BFA and MFA, he graduated in painting from Azad University. His first solo show was held at Azad Art Gallery in 2001, bringing to Iranian visual arts field a new approach that he has followed ever since; that is, depicting people's visages with the most accessible tools. The subject and the means he uses to render accord with each other: creating portraits of people in the society with a pen. He describes his frequent use of this tool in his works as:

"I found the pen to be the best tool to express the persistence of darkness in these bad moments. Its fine tip multiplies the time I need to create my works. Moreover, it delivers my voice to the viewer with more intimacy because its marks are familiar to them. In fact, I broke a barrier that artists generally considered necessary to separate themselves as intellects from the audience as the public."

Humans in Morshedloo's works are frequent and interconnected figures. Sometimes, as in a photograph frame, they are cropped from the head, hand, or torso. Sometimes their hanging feet are the only visible part of their body on the top of the frame. Sometimes they stare, while other times, they avoid facing the viewer and get lost amid a crowd of bodies. The naked bodies of men are visible in the multiple frames installed next to each other on the gallery's biggest wall. They seem not to be created for the viewer standing before them. Instead, the figures are looking away through their interactions, or they have even turned their back on the viewer. In some of the works, the figures, with gazes as bare as the bodies, are separated from the crowd with the tile patterns in the background.

It seems that "Golestan," as the title of this show, is inspired by the patterns of Golestan Palace tiles, a sign also evident in the artist's previous works. For today's audience, these patterns are visual elements that bring life to their selfies in the Golestan Palace, more than they would remind them of history. In Morshedloo's "Golestan," colorful tiles and shining mirrors are represented in order not to leave the naked human bodies and the severed heads and hands of the sheep without any background. This is a multifaceted challenge that the viewer faces when looking at the paintings again; the questionable coexistence of human bodies and an empty sofa with a cat sitting in front of it while staring at the viewer, all along with the severed heads and hands of the sheep. It seems they all have one feature in common; passivity: alive but lifeless faces that appear passive and devoid of any identity as an object, a will that has been taken away, allowing violence to dominate a violent society even more.

Ahmad Morshedloo | Untitled | 2019 | pen on cardboard | 90 × 120

The severed head of the sheep at the show's entrance reminded me of Linda Nochlin's book "Body in Pieces," where she described "the fragments as a metaphor of modernity." Nochlin understands fragmentation, mutilation, and destruction as fundamental metaphors of visual expression. Nochlin writes:

"Géricault's rather matter-of-fact if poignant depictions of Napoleonic anti-heroes, whose bodies are quite literally 'in pieces' – broken, amputated – serve to remind us that there are times in the history of modern representation when the dismembered human body exists for the viewer not just as a metaphor but as a historical reality."

And continues:

"By laying them out, in perspective, on a horizontal surface, Géricault consigns the mutilated heads to the realm of the object, plays their erstwhile role as the most significant part of the human body against their present conditions as lifeless, gruesome fragments, deployed on a tabletop like meat on a butcher's counter or specimens on a dissecting table. "

The juxtaposition of all these images on the walls of Navahi Projects is reminiscent of the similarity of humans to these objects and creatures. After his previous solo exhibition "Null" at Azad Art Gallery in 2019, an immediate visit to this exhibition allows the viewer to review the artist's approach and works throughout his artistic career. Morshedloo's artworks have been presented in several group shows in Iran and around the globe, including the 56th edition of the Venice Biennale in Italy and the Bonhams Online auction in 2021.

Sources:

-

www.honarmrooz.com

-

Nochlin, Linda (1994). The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity. Thames and Hudson Inc.

Cover and slider image:

- www.navahi.com