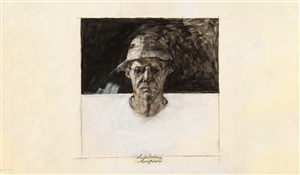

Parviz Tanavoli, an Artist Who Creates "Heech"

23 Dec 2021Original text in Farsi by Shamim Sabzevari

Translated to English by Omid Armat

Parviz Tanavoli's enthusiasm for the popular and traditional heritage of Iran and his open approach to the process of creating an artwork, have made a balance in his art and elevated him beyond a specific cultural context. Being known as "the first modern sculptor of Iran", he developed his subjective language which is undeniably modern and absolutely Iranian. He neither imitates Iran's visual vocabulary nor ignores it; he links it with Western contemporary art, thus creating and developing his own art. His tendency towards form and elimination of function has released artistic tradition from its mythical aura. Many of his ideas are derived from Iranian culture appeared in myths, historical and epic poems, rugs and handcrafts, reliefs, and old pieces of iron and pewter. He aimed at creating an Iranian visual vocabulary which is connected to Western modern art, but how successful has he been?

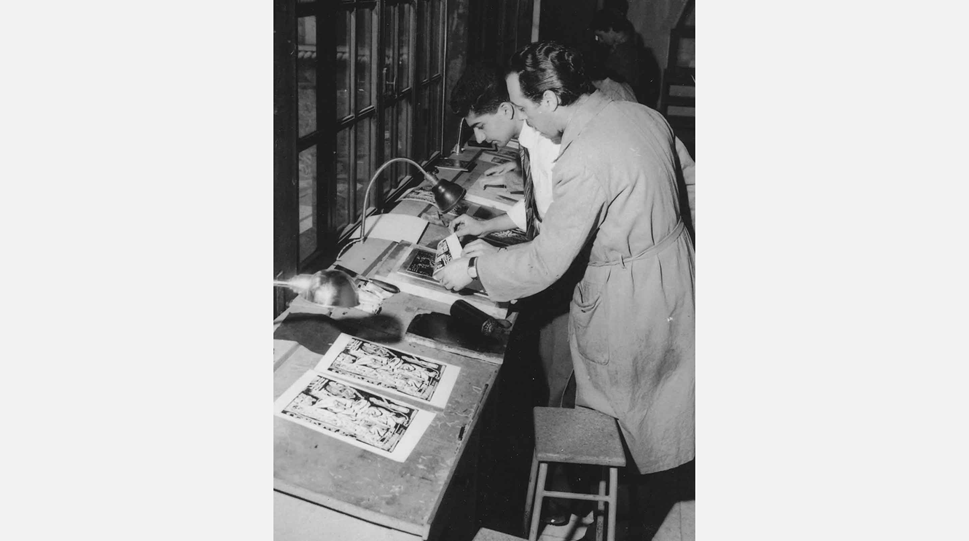

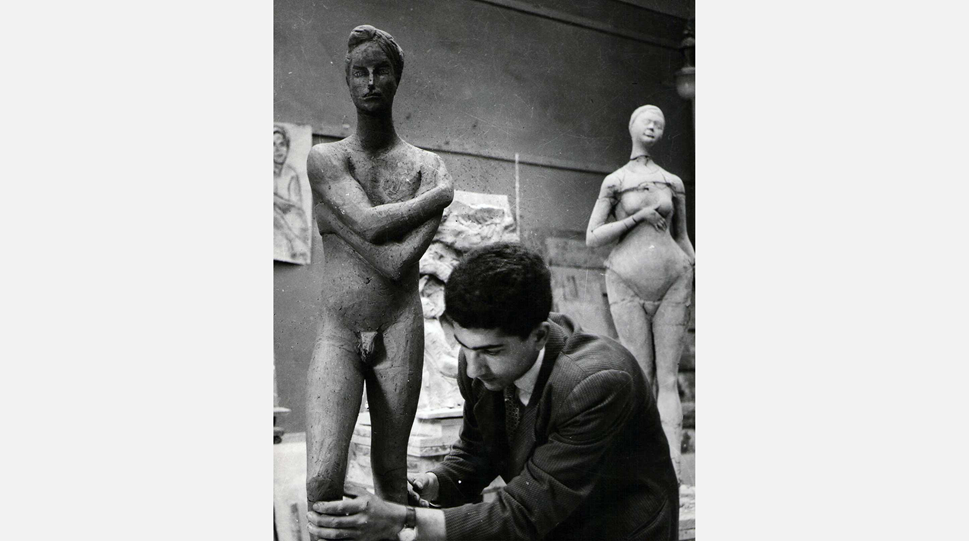

Parviz Tanavoli | Brera Academy | 1955-1957 | Image copyright: parviztanavoli.com

In the early 1930s, when the Fine Arts School opened, Tanavoli started his art studies by attending the sculpting course at this school. He then moved to Italy to continue his studies and training in the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara for two years. He moved back to Iran afterward but went to Italy again in 1957. This time he trained in sculpting at Brera Academy under the supervision of Marino Marini, the famous Italian sculptor, and during the same year, he was invited to teach sculpture at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design in the United States.

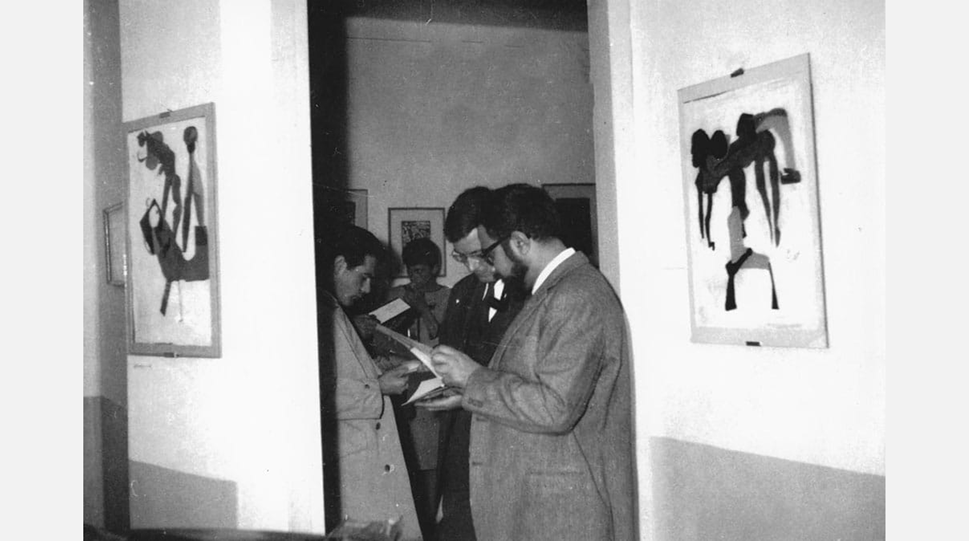

When he returned to Iran, he rented an apartment in Abbasabad district of Tehran and established his personal atelier called Atelier Kaboud. The studio became a favorite meeting place for young artists and intellectuals in which the "Saqqakhaneh School" was formed at the beginning of the 1960s; that is a movement formed by young artists, most of whom were educated in Western countries and wanted Iranian art to match the Western art language. By using international visual and formal strategies, the movement aimed at creating artworks inspired by Iranian folklore art and traditional cultures.

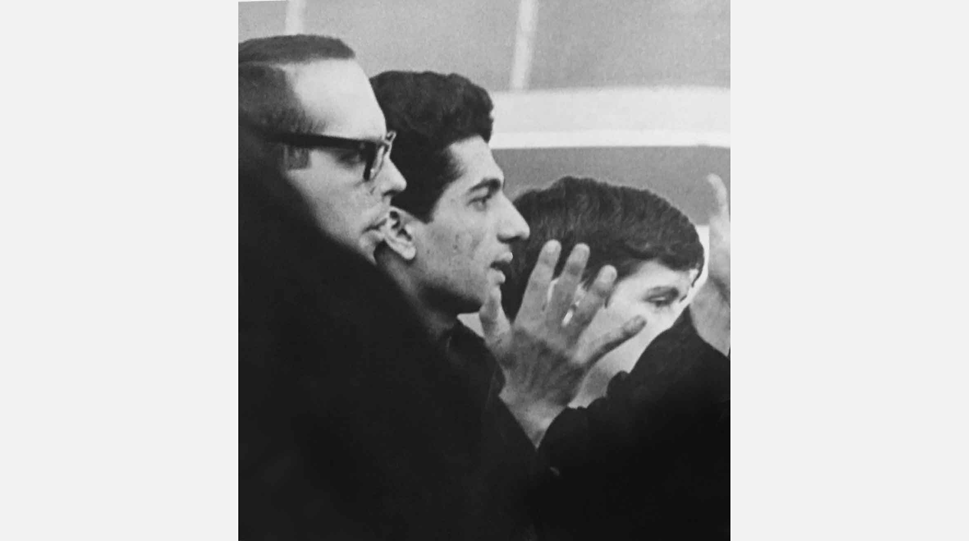

The Opening of Parviz Tanavoli's Exhibition | Kaboud Atelier | 1959 | Image copyright: parviztanavoli.com

Parviz Tanavoli was one of the main founders of Saqqakhaneh School. He, along with artists such as Charles Hossein Zenderoudi and Faramarz Pilaram, was specifically interested in exploring Iranian visual traditions and their reinterpretation in the context of modernism. His works consisted of a huge variety of Iran's cultural signifiers, including particular and popular elements from the ancient times to the present. He spent many years researching Iranian traditions and collecting handicrafts such as locks, spells, gravestones, ornaments used for horses and camels, rugs and textiles, ceramics, and also the magic of letters and numbers which influenced his work profoundly.

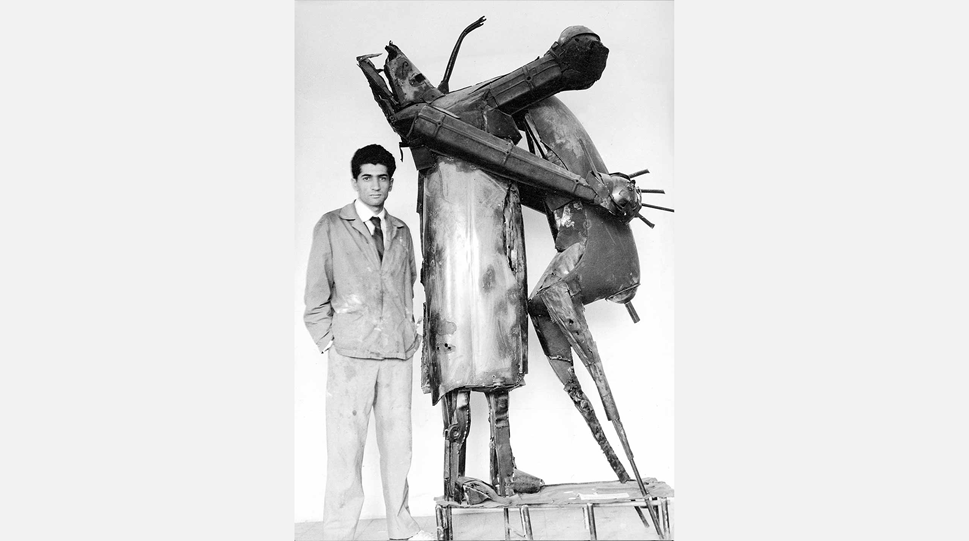

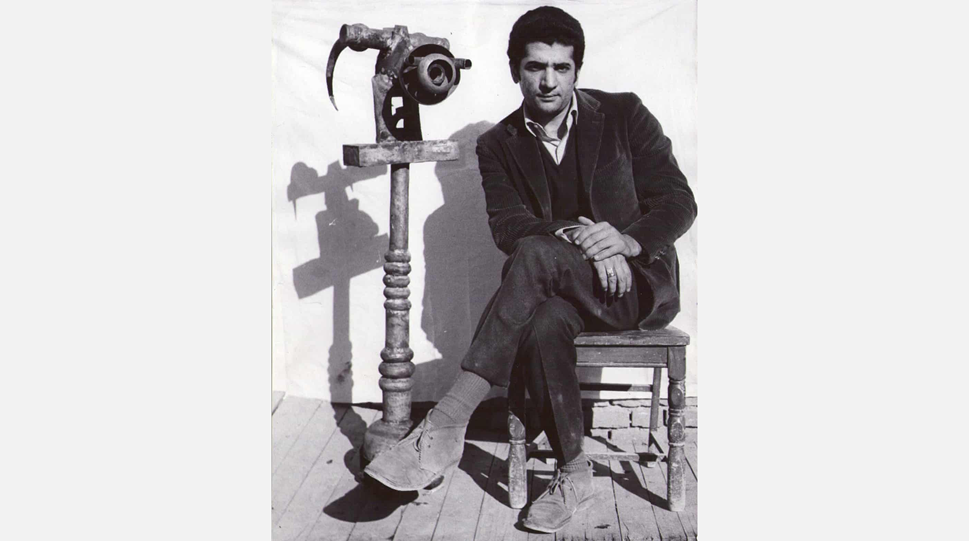

Tanavoli founded objects and pieces at local foundries, smithies, and welding workshops and included them in his sculptures, ceramics, and paintings. When he returned to Iran, he was still under the influence of his teacher, Marini, but he gradually formed his own style in accordance with Saqqakhaneh School and used different popular objects in creating his artworks. His art, which was beyond the time's comprehension and taste, surprised many advocates of old traditions and caused them to stand against it. As Tanavoli said:

Before us, artists were proud to follow Picasso or Cezanne, but we were different, we had our own school, our own art… I didn't want to follow westerners, we wanted to be more Persian, so I used all the tools around me: locks, grills... Gradually I created my own anatomy, anatomy for an artist of an Islamic background. (The Guardian | Parviz Tanavoli: Iranian artist who made something out of nothing)

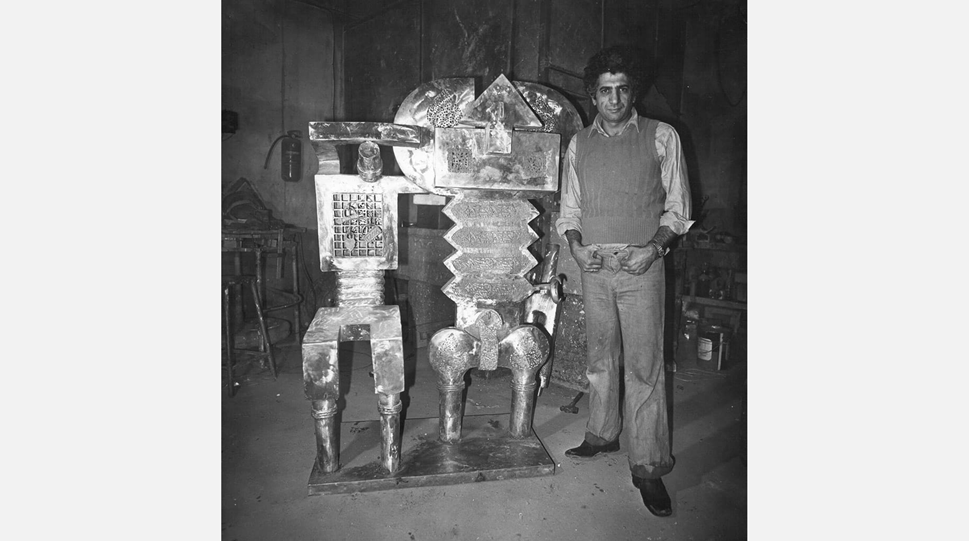

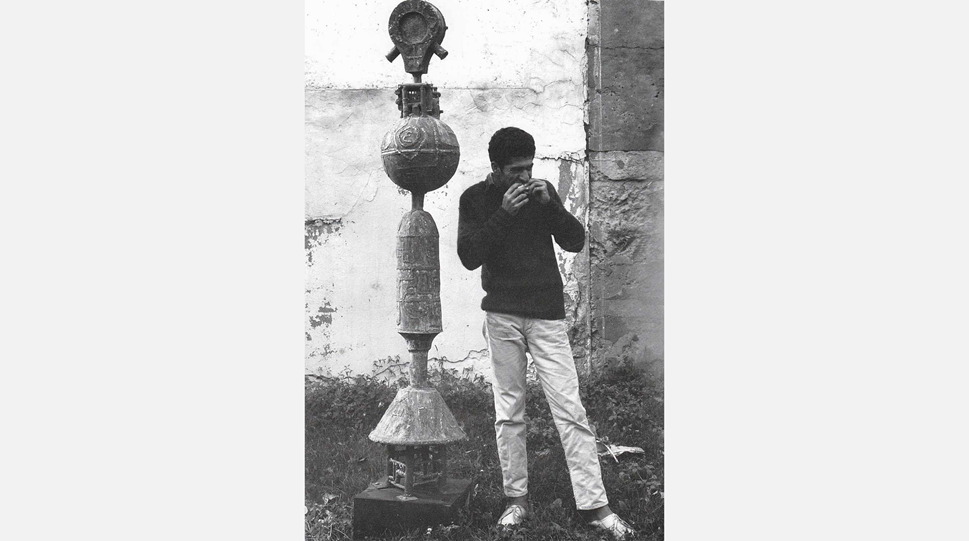

Parviz Tanavoli | 1963 | Next to Copper Beloved of the King | Seyhoun Gallery | Tehran | Image copyright: parviztanavoli.com

Many Iranian artists and intellectuals disagreed with his method of dealing with tradition and formal imitation, but it is worth noting that during the same years (the 1950s and 1960s) in England and particularly in the United States, artists following the Pop Art movement found a new field of creativity by utilizing the forms of popular and consumable objects and pieces; this was a "commercial" art that could be considered as some type of popular art of the ordinary people. In fact, the Pop Art movement wanted to show a glimpse of life and dreams of people in the West by using a variety of unartistic sources prevalent in their culture and daily life.

In an interview with Parviz Tanavoli, we asked him: "How do you evaluate your connection to these artistic and cultural movements?" He responded:

"There is no connection. You'd better refer to the introduction I wrote in Heech book. My handwriting is attached."

Parviz Tanavoli's Handwriting

Although the sources used by Pop artists were different from the ones used by Iranian artists, the cultural relation between them and the influence of Pop Art on Saqqakhaneh School cannot be ignored. By utilizing Iranian popular tradition and culture, artists who followed Saqqakhaneh School wanted to create a new art that could acquire notable significance on a global scale. Therefore, Saqqakhaneh School, which was formed along with the pop culture in Europe, showed references to its own context through employing pop culture and what belonged to the life of an Iranian person. Not surprisingly, Tanavoli's artworks attracted Abby Weed Grey's attention in 1961. Grey, who became Tanavoli's sponsor, had noticed his work through the Iran-America Society. She organized his art residency at Minneapolis Art School in 1962 and became his top art collector.

Parviz Tanavoli | 1961 | Grey Gallery | Minneapolis, U.S. | Image copyright: parviztanavoli.com

The idea of creating a series of sculptures entitled "Heech", which have become Tanavoli's artistic signature over the years, came into his mind right after the failure and closure of his 1965 major show at Burgess Gallery. One of the works on display at the exhibition was a handmade rug-like design, part of which was carved and replaced with a Persian water pitcher. It was like a tile-layered recess within which a valuable object is usually niched, but this time it was used for placing a water pitcher. The coincidence of a daily object with something associated with a quasi-sacred quality, shocked the visitors. "heech" was his response to the closure of his show; as he has stated:

"I was disappointed. I thought I could not continue like that – nobody liked my works [in] those days, not even intellectuals. I didn't hear even one compliment. They hadn't seen things like that." (The Guardian | Parviz Tanavoli: Iranian artist who made something out of nothing)

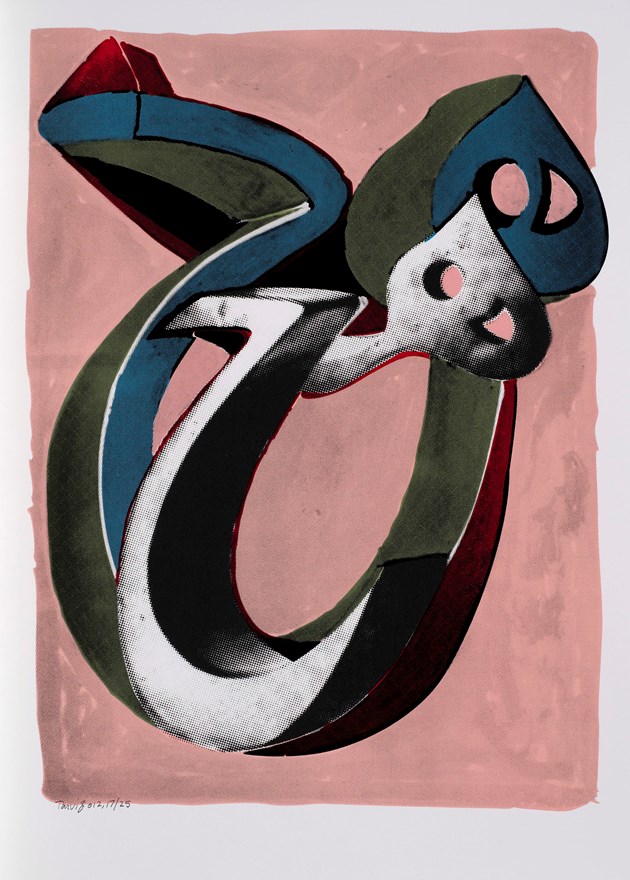

He used the word "Heech" (which means 'Nothing') and designed it with Nastaliq typeface so as to react against the overuse of calligraphy in Saqqakhaneh School and calligraphic painting (a field which he thought had lost its purity and become increasingly commercialized) and also to raise objection to people, institutions and art market that approve of hollow imitation and repetition.

According to himself, he has created hundreds of "Heech" sculptures, some of which lean on a chair, some melted and some standing next to each other like a couple. So many years that he spent on creating Heechs and the large number of Heechs that he made over these years caused the whole idea to ascend beyond his initial protesting phase. As he said:

"The word heech alone, it's not that heech is just 'nothing', it's a lot of things, as far as its meaning is concerned and as far as its shape is concerned." (The Guardian | Parviz Tanavoli: Iranian artist who made something out of nothing)

Parviz Tanavoli | Pink Heech | 1970 | fiberglass | 157 cm

The idea and creation of Heech series may be scrutinized from different aspects, the first of which is the writing form and the use of Nastaliq typeface. These features reflect Tanavoli's main goal: using Iranian visual traditions to make an innovative artwork. This was the idea that calligraphic painting and Saqqakhaneh School artists such as Zenderoudi, Pilaram, Sadegh Tabrizi, and Mansoureh Hosseini followed at that time.

Aside from this movement, at the same time, several Western artistic styles were inspired, in different ways, by words and texts. We mentioned Pop Art earlier. We know that pop culture is linked to language. Words are linked by nature to human beings' daily lives. Anything, like art, which is a symbol of human beings and their life, is based upon language. In Pop Art and Conceptual Art specifically (such as word art or text art), words play a significant role in challenging one of the most famous rules of modernism; that is visual arts should detach themselves from words and literature to evoke more instinctive and vivid responses in the viewer. The new attitude also challenged the boundaries of art. This was what René Magritte, the famous Surrealist artist, attempted differently by painting "This is not a Pipe" in 1928.

Many artists during the 1960s and 1970s wanted to relink the visual arts with the narrative and revive the great tradition of developing dialogue through art. Artworks of this kind were not comparable to any conventional artwork of that time; these experimentations were carried out by utilizing language, and the viewer encountered some words, phrases, or a literal definition on the canvas or the gallery's walls. In other cases, an abstract aspect of a word was formatted in a figurative or formal appearance: Roy Lichtenstein's huge painting in which the word "Art" was painted in a large size or what Keith Arnatt, the British painter, put on display at Tate Modern in London in 1972; he wrote, "Keith Arnatt is an artist" on a big white wall. The art movement during the 1960s and 1970s was against the convention of creating meaningful and beautiful artworks and challenged the meaning and the position of art. The new art communicates its message without any medium and what is more suitable than words to communicate meanings? So Tanavoli followed the same path as Western Conceptual Art.

Iranian art tended then towards becoming global while remaining Persian; as a result, art movements in Iran were neither stably concerned with traditions nor had enough dynamism and innovation related to the era. Due to the saturation of the Iranian visual arts field by calligraphic painting and Saqqakhaneh artworks, there was little room for alternative thoughts. In addition, when Saqqakhaneh was determined as the official artistic mainstream of the country, the innovative possibilities were diminished at the cost of satisfying the art institutions. Although Tanavoli created "Heech" to react against the then art movements in Iran, his protesting activities were based on the very same field. Using Nastaliq typeface to create a sculpture with "nothing" as its message is just another display of the same repetitive field. On the other hand, this art movement was conforming to Pop conventions that were getting established in contemporary art; even if the Iranian artists of this movement were not aware of it. Therefore, Tanavoli could preserve his link with Iranian art movements and get noticed by the Western art world at the same time. The formal simulation of Iranian visual language with European modern art provides these artworks with necessary orientalist features that help Western viewers understand them.

Parviz Tanavoli | Heech on Heech | 2012 | screenprint on paper | 70 × 50 cm

Moreover, Tanavoli's personal idea of nothingness and hollowness had a nostalgic content. As he said himself, Rumi's attitude towards the world has deeply influenced his understanding and "changed his life forever." Tanavoli believes the idea of these sculptures has roots in Rumi's poems and that they reflect the Sufism belief which says God creates everything out of nothing. Regarding Rumi as his first mentor, Tanavoli considers this poem as a model for his career:

The world is just nothing and its residents are nothing / You're nothing and do not get involved in pointless things.

You know what is left after your death? / Love and affection and the rest is nothing.

It may seem strange and radical to say that an artist creates "nothing", but Tanavoli has tried to repeat the process of developing an idea and making artwork in the context of creating "nothing"; that is why the content and structure are, to some extent, similar in all artworks, but the form and the narrative differ from one to another. Different pieces of Heech vary in size and medium: bronze, fiberglass, and neon. Some of them have a figurative form and simulate the human's body, positions, and features. For example, a Heech that comes out of a box, the other melts down on a chair, lies back, and embraces another Heech like a beloved. In fact, "Heech" is not just nothing, it has an irony that even challenges the concept of nothingness, and covers, to some extent, the repetitive aspect of the pieces. This reflects Tanavoli's narrative and idea in his way of dealing with figures, playing with forms, and utilizing familiar and nostalgic content to express a personal concept.

Breaking the Molds of Parviz Tanavoli's Sculptures | 2021 | The Artist's Workshop in Niavaran District, Tehran

On November 20, 2021, several molds of Tanavoli's sculptures, including "Heech", "Hand", "Lovers", and "Persepolis" were broken in the artist's house. We asked him: "Now that the molds of Heech sculptures are broken, has the idea of "Heech" come to an end too?" He responded:

Never! The idea of "Heech" will last. Breaking the molds is done only to support the rights of the owners of the "Heech". Tens and hundreds of these owners in Iran and abroad were waiting for these molds to be destroyed. It was not easy for me to break them and I felt bad the day I was doing it. But I had no other choice. Even now that I am alive, I have seen many copies of my Heech sculptures! Although we have legally stopped forgers, no one knows what could happen if I had died and the molds would have still been there?

Slider image 1: Parviz Tanavoli | University of Tehran's Studio | 1965 | Image copyright: parviztanavoli.com

Slider image 2: Parviz Tanavoli | Print Studio | Carrara | 1957 | Image copyright: parviztanavoli.com

Slider image 3: Parviz Tanavoli | Jacques Lipchitz's Speech | Minneapolis College of Art and Design, U.S. | 1963 | Image copyright: parviztanavoli.com

Slider image 4: Parviz Tanavoli | Niavaran Studio | Tehran | 1972 | Image copyright: parviztanavoli.com

Slider image 5: Parviz Tanavoli | Next to Farhad and Ahoo | 1960 | Image copyright: parviztanavoli.com