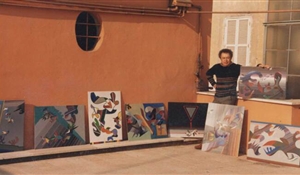

Manouchehr Motabar, An Artist Who Is Concerned with the Human

05 Mar 2022Original text in Farsi by Shamim Sabzevari

Translated to English by Omid Armat

Introduction

In creating his artworks, Manouchehr Motabar has always tried to use elements and realities of the world; his brief encounter with things, which is a result of his innate and lyrical attitude, has led to an expressive approach to painterly representation, mostly reflected by dominance of space over human, and expressive, strong, illustrative lines that have distanced his art from realism. Motabar's work is based on his profound drawing knowledge and he may be undoubtedly considered the artist who consolidated Iran's recent drawing art. During various stages of his artistic activity, Motabar has tried different methods of drawing-like paintings which is a determinant feature of his subjective style. His use of expressive charcoal lines, minimum application of paint, and concentration on black, white, and grey have created drawing qualities in his artworks.

Manouchehr Motabar | Untitled | 2019 | silkscreen | 70 × 50 cm

Although Motabar has changed his subject during different stages of his work, he has always maintained his subjective attitude, avoided objective narration, and concentrated on representing his lived experience. He has chosen to use this simple, but strong structure to express human feelings. In his paintings of alleys and streets, scenes of the Iranian Revolution and the Iraq-Iran war, cemeteries, women in the veil, and his self-portraits, Motabar has looked for humans in order to study their features and the deepest parts of their selves. Shocked and thinking humans in his paintings, with their grey colors, have created a depressing and gloomy atmosphere which not only guides the viewer to a happening in the past but also suggests an existentialistic interpretation of human contemporary life. This is why viewers of his works experience personal feelings and subjective understanding, just as the artist has represented his subjective perception of an occurrence or a phenomenon; this has been the encouraging factor for him to continue creating artworks, because he cares about making dialogue with the viewer, not just creating and displaying artwork. He says: "I realize things. When I see other people like them, I feel that what I have said is being understood." For him, the painting experience is a kind of discharge. In his words: "your mind has to become laden. It is like sorrow; when you are laden with sorrow, you cry, or when you are very happy you look for people to talk to. You express your feelings, there is nothing else you can do about it."

Childhood and Youth

Manouchehr Motabar was born in 1936 in Shirz, Iran. He did not have a rich family, but all his family members were interested in art; his father was a goldsmith and had beautiful handwriting, and his mother, who was raised in a family with a great taste in art, was interested in poems and calligraphy. In school and after getting familiar with pencils and pens, he became interested in painting. In the fourth grade of school, he learned drawing and painting from Naser Namazi, an art teacher and one of the students of Kamal-ol-molk. Over these years he was eagerly occupied by painting and copied the works of European painting masters. During his last years of school, he had the opportunity to meet Sadr-al-din Shayesteh Shirazi and watch his realistic works closely. Naturally, his interest in a figurative and realistic style determined his path which he never left. In 1948 he received a diploma in natural science and finished school.

Education

In 1956, Motabar attended the entrance examination for the Faculty of Literature at the University of Shiraz. He studied the English language and literature for a short while, but his passion for painting changed his course. He returned to Tehran and attended the entrance examination for the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Tehran. He ranked second and started studying painting. During his years at the university, he was friends with Gholamhossein Nami, Mohammad Ebrahim Jafari, Ghobad Shiva, Morteza Momayez, and Farshid Mesghali. The defective scheme of teaching art at Beaux-Arts de Paris was still being followed in the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Tehran. Although teachers in this faculty, including Mahmoud Javadipour, Javad Hamidi, Behjat Sadr, and Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam, had their own specific methods of teaching art, Ali Mohammad Heydarian, who was Kamal-ol-molk's student, determined the main direction of teaching at the faculty.

Manouchehr Motabar | Untitled | 1974 | oil on canvas | 80 × 80 cm

Motabar was deeply influenced by Ali Mohammad Heydarian. Heydarian was experienced in naturalization and taught still life, landscape, and figurative painting to students; these were the basics of drawing and painting. Motabar respected him and painted under his supervision. Motabar had his own way of using colors; sometimes he used more paint and created paintings similar to Impressionist paintings. Heydarian did not approve of these methods and told him: "you're becoming too much of a modernist."

As Motabar said:

"I knew that I had to learn the basics of painting. We had to compensate for what Leonardo da Vinci did five hundred years ago and we didn't. To do that, we had no way, but to learn the basics of drawing. Even then, unfortunately, Iranian students didn't care much for drawing. Most of the students didn't even acknowledge Heydarian as an art teacher; because they were fond of Modernists like Chagall, Renoir and Impressionists… It's because of my working background that I am still remembered. Once I became a student, I started to learn drawing because I knew we are weak in drawing and we have no one from the past to consider as an example."

His emphasis on drawing and its principles always remained in his art and formed his future artistic career path.

During his years at the university, Motabar focused on drawing, naturalization, and studying works by Rembrandt, Ingres, Daumier, and Toulouse-Lautrec. Eventually, he found his personal language by benefiting from his teachers' different teaching methods. When he first started, it was just about a passion that he had for drawing and painting, but after he entered the university he realized that he experiences some kind of discharge while painting. When he was a student, he tried to illustrate the beauty of nature and share it with people. It was important for him to make dialogue and establish a relationship with people. He wanted to find an audience; so he found his way of expression, with which he could talk, express his pain and happiness and share his ideas with people, and most importantly, deal with his loneliness. This loneliness is what plays an important role in his artworks. His relationship with Behrouz Golzari had a great influence on this matter. Motabar said: "At first, I got surprised when I saw someone drawing while sitting in the midst of the street, but then I learned from him."

In 1961, he got employed contractually in the ministry of culture and art and worked in the graphics division, where Sadegh Barirani was the manager. During his employment, Motabar designed posters and cooperated with "Golbang" and "Art and People" magazines. Starting his career as a professional painter since he was a student, Motabar, under the recommendation and encouragement of Houshang Seyhoun, dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts, ran his first exhibition in 1962 at the faculty. The next year, he exhibited his works at Iran's Youth Association. In 1966, he finished college and received his bachelor's degree.

Career

After university, he persistently continued drawing and painting and arranged two solo exhibitions in 1967 and 1968 at Iran-America Society. Working at the ministry of culture and art did not satisfy him, so he requested to be sent to art school as a teacher, but before getting accepted, he had to wait a few years, during which he was sent by the ministry to Isfahan to render a design. Becoming fascinated by alleys and the old structure of the city, he started to depict its neighborhoods through drawing. He exhibited the Alleys series at Seyhoun Gallery. He, then, focused on still life and flowers. He selected his subjects from daily objects and other things around him. He could make a dialogue with the simplest objects, even if it was just a vessel or a vase. For example, Geraniums vases that he had put along the corridor of his house were among his first subjects, so he used painting as a basis for analyzing their leaves' forms. His insistent formal analysis sometimes led to abstract paintings.

In order to improve his painting skills, he decided to continue his academic studies; so moved to the U.S. in 1971 and signed up for drawing classes at the Art Students League of New York; this was a six-month compact course, during which students were instructed by highly experienced teachers and it was mainly concentrated on studying and drawing human's body. Living and studying in New York was an opportunity for Motabar to visit museums and galleries and to get familiar with American art and the world's contemporary painting. As he said:

"During my first trip to the U.S., I saw works by Edward Hopper. I was easily attracted to the solitude and silence of his works, his convenient rendition, and the shadings he applied."

Manouchehr Motabar | Untitled | 1976 | oil on canvas | 120 × 80 cm

He moved back to Iran in 1972 and arranged an exhibition at Seyhoun Gallery with the depictions that he had drawn before and the results of his studies in America. These works included landscapes of old and empty alleys with thatch walls without any exaggerated perspective, which reminded the viewer of distant, but appealing and lasting memories. He wanted to display a section of the world in a timeless and placeless context in the simplest possible way. Eventually, he started teaching at Fine Art School in 1975 and continued until 1996. Being trained as an art teacher and given his background in the U.S., he knew the method of teaching art in Iran was very defective; so he tried to use western methods. As he said:

"In our society, teachers raise disciples; it means that they submit the student to the tasks that they haven't experienced themselves, or they want the student's work to be similar to their own work. This eliminates the student's character. I have been teaching for many years, yet none of my students work like me. They have their own working style. I tried to broaden their vision and to cast light on their way so they can find it." Masoumeh Mozaffari and Rozita Sharafjahan are among Motabar's well-known students.

Motabar went back to the U.S. in 1977 and attended another drawing course at the Art Students League of New York. He, then, returned to Iran and ran another exhibition of the results he had achieved. This exhibition included portraits, still lifes, paintings of flowers, and landscapes of alleys and streets. The mutual quality of these works was their precise drawing with aggressive, strong, rapid lines. Some of the works were simplified to the extent that presented a relatively abstract composition. Motabar moved to America for the third time in 1978 and studied art education at Indiana University. He participated in two group exhibitions in the same year. Due to financial problems, Motabar had to leave university; so he returned to Iran in 1980.

His return coincided with the events after Iran's 1979 revolution and the war with Iraq. As the majority of Iran's people were engaging with political and social issues, new subjects started to appear in Motabar's artworks: social content, grief, disasters, and intense conditions caused by war. In addition to the subjects he chose to visually reflect these issues, the major influence of this situation on his work was the dominance of blacks and greys, and his minimal use of colors in the painting. Motabar believes artists' style of expression and creation of artworks is not static and keeps changing in relation to their living experience. Motabar, too, as a sensible artist, adapted his attitude to the conditions he was living in.

Manouchehr Motabar | Untitled | 1999 | acrylic and charcoal on cardboard | 30 × 40 cm

Over these years, he continuously focused on space and subjects in his works; he chose women in veils, hearses, funerals, and mourning women in black and cemeteries as his main subjects. In fact, death, loss, and anything that indicates death, loneliness, and darkness became the primary theme of his artworks. In this sense, an empty chair, an old alley, and a dark, grey space are also associated with the same meanings. He said about the dark atmosphere that prevailed in the era:

"I feel that our era has turned into a grey and black space and everyone is living under a dark shadow cast by grief and sorrow. I wish they see death so close that they appreciate their living moments, and hear and believe the singing song of passion in their lives."

Motabar uses both subjective and objective matters in the process of creating his artworks. In order to appropriately depict the human figure, he asked his relatives (for example his nephew) to hold a veil and stand as a model, so he could illustrate the body in any position. He had a wealth of anatomic experience and was proficient at drawing; his drawing skills were fully apparent in his illustration of body mass, body organs under a veil, and even the children being held by women in veils. During these years he drew pictures of pregnant women; a subject clearly different from mourning women in black. For example, he rendered a woman looking out the window while a light beam entered the room. he said about the formal and conceptual differences:

"All of these images were surrounding me, I just drew them. For me, a pregnant woman is quite a meaningful subject. Her form of standing and perseverance is beautiful. Someone else may not care about this, but I do and I like it."

He was influenced by events happening around him within the society, and each one, as a mutual lived experience, was somehow reflected in his works. This can establish a relationship between the artwork and the viewer, and between the viewer and the author. It can also create dialogue and lead to various interpretations of the artwork. Although the artist has developed an idea and represented it in a particular form, the viewer can come to a personal perception of the artwork due to the visual qualities of the paintings and the social narrative that lies behind them. At this stage, the artist or author loses importance and the picture itself communicates. Motabar has admitted this; as he said:

"Things that depress you; you picture them or write about them, so you get rid of them, but you're giving them to others who may have experienced them too. I think it starts with memories; things that have remained in my mind and I am now slowly letting them out. As André Gide once said, "let the importance lie in your look, not in the thing you look at." Many things exist, but our look must make them different, must be impressive… My painting 'A Pregnant Woman Looking Out the Window' means looking for tomorrow. We all do this, so the painting itself can talk. It can be understood by the viewer as: what is she thinking about? Is she thinking about tomorrow? Does the baby like to come to this world, or not? What is waiting for the baby in the future? These are the words the picture itself brings to mind. I don't exist as the author anymore. I have created and left behind a work to be settled into people's memories; a work about the days I lived in, and have passed."

Motabar attended the Monaco International Painting Exhibition in 1984 and 1985. In the second year, he was awarded the prize and the honorary diploma. In the same year, one of his works went on display at Joan Miró International Drawing Exhibition in Barcelona. He was asked to teach at the Tehran University of Art in the middle of 1980s. During the late 1980s, he displayed some of his artworks in group exhibitions. In 1987, for the first time after Iran's revolution, he arranged his first solo exhibition at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. He also exhibited his works in 1989 at Pafar Gallery, and in 1990 at Classic Gallery.

Manouchehr Motabar | Untitled | 2000 | acrylic and charcoal on cardboard | 36 × 46 cm

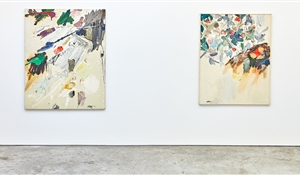

During the 1990s, colors gradually became more apparent in his work; he used bright green, orange, and red colors in addition to black and white. He said about this change in his attitude:

"In addition to their aesthetic significance, colors play another role in my works. In other words, colors break the grey space of my works, and they sometimes bear symbolic roles. Green is a symbol of religion, and red is a symbol of violence. Colors also give my work a window to breathe. Moreover, minimal use of colors puts more emphasis on the absence of colors and on the blacks. Colors are usually applied in the final stage in a way that they cannot be replaced by any other colors."

He used colors whenever he felt the necessity to. He even combined charcoal with oil paint. It is some kind of an inevitable necessity, in his words:

"there is a necessity for anything that exists, and it can certainly do something."

Over these years, some kind of geometric segments gradually appeared in Motabar's work. In his dark paintings, the main role is played by colors and the intense contrast between light and dark shades. In search of new forms and compositions, he surrounded his subjects with frames drawn with lines and colors, thus arranging the space orderly. Moreover, human subjects shrank and the space around them became bigger. Aliasqar Qarabaqi writes about these artworks:

"...He paints what people left in his mind as memories. Since no one can remember every single element of memory, he designed a structure for remembering which resulted in his specific form of drawing. He has experienced enough with this structure so as to present it as a practical way for recalling memories. Because these works are created to depict escaping moments of life, they are filled with events, and because he wants to gather these events in a painting, he needs some sort of mathematical precision, some of which he keeps and eliminates others in order to render an artwork independent of literature's support."

During the 1990s, Motabar performed solo shows at Arya Gallery (1993) and Sabz Gallery (1995). In 1995 and 1998 he exhibited his works in his own studio. He also arranged a solo exhibition at Zurich School of Architecture in 1998. In the same year, his works were presented in a group exhibition called "Iran's Contemporary Painters" in Texas, New York, Chicago, and Kiev. In 1999 and 2000, Assar Gallery hosted two shows of Motabar's works. Over these years, he attended Iran's Contemporary Painting Biennial and Iran's Contemporary Design Biennial, both of which were held at TMoCA.

Manouchehr Motabar | Untitled | 2004 | collage, acrylic and charcoal on cardboard | 47 × 47 cm

In 2001 a commemoration and review of Motabar's artworks were held by the Association of Iranian Painters. Pooya Aryanpour made a film of Motabar's life and artworks. In 2002, Motabar was invited to teach at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Tehran. In 2004 a collection of his artworks created between 1961 and 2004 was published in a book by Nazar Publications. A documentary film about Motabar and his artworks was made by Farivar Hamzeyi in 2005. During the years before the Iranian Revolution, Motabar was occupied by the Pigeons series. He, then, focused on crows as his new subject in the 2000s. He drew quick sketches of a crow's figure or took a photo of it, and then he completed his work using both the sketch and the photo. He tried to represent the features of crows rather than just picturing an overall form by rendering its components. He also focused on himself instead of events around him, which led his work to more complicated and expressive self-portraits during these years. At this time, he started creating portraits of Iran's famous figures in addition to his repeating motif of an old Jewish man's visage and hands inspired by an artwork by Rembrandt. He also continued dividing his works' surfaces with color spots and frames to the extent that they seemed like abstract paintings. He was more concerned with the expressive qualities of his work rather than its form. So at this point, annotations and text collages appeared in his artworks as a part of his visual expression. In other words, he decided to decrease the formal narrative and replace the image with text.

Manouchehr Motabar | Untitled | 2009 | acrylic and charcoal on cardboard | 60 × 60 cm

Although Motabar has changed his subjects many times, a constant logic is visible throughout his whole career path. During fifty years of painting and drawing, Motabar chose elements and narratives of his personal and social life and formed and repeated them. With his unique style of drawing and under the influence of masters of art history, such as Rembrandt, Daumier, Bacon, and Hopper, he pictured still lifes, old, traditional alleys; he presented narratives of death, and depicted mourners as women in black veils; he represented still nude bodies, crows and pigeons; and more than anything else, he created self-portraits, maybe more than three thousand according to himself. The common point between all of his works is that a sign of "human" is always discernable. Human is the main element of his works; his constant rendering of human visages and figures has become an important part of his artistic creativity process; but Motabar's humans are calm, silent, thinking, and introverted, without presenting any specific type of personality or any sign of personal features. The concept of "loneliness" may be traced throughout his work. This loneliness is sometimes narrated realistically by depicting recluse humans or detached objects, and sometimes the overall formation of the space and the applied shades evoke the same feeling.

According to Motabar, his familiarity with the paintings of humanist artists, like Hopper and Bacon, has certainly influenced his attitude. He is inspired by the solitude and the dominance of space over humans in the works by Hopper and White; that is a human left alone in architectural space and surrounded by stillness. Although his manner and style of work are different in many aspects from the expressive and deformed paintings of Bacon, signs of Bacon's ontological attitude are detectable in Motabar's artworks.

This kind of approach to the lonely human (even in the middle of the crowd) so desperate to know themselves and their existence, is accompanied, in Motabar's work, by some sort of misery and the dominance of grey shades. Motabar has remarkable skills in picturing physical features of the human, such as the body and its muscles, and the anatomy of the body in general. Considering the body's form and its details may be a way to discover its underlying layers; a way through which the artist has tried to establish a link with the human (in its objective sense and regarding its appearance) in order to acquire an understanding about the human (what humans perceive when they encounter themselves or others as subjects and try to discover them). This is how Motabar attracts viewers; he attracts them with the visual, objective forms and wants them to explore the artwork, then he asks them to ignore the attractive body and the human's perpetual concerns, so as to look for issues such as loneliness, sorrow, death, existence, and anxiety.