Hugh Mangum's Negatives; Narrators of Black History

30 Aug 2022Hugh Mangum was born after the American Civil War. He lived in the south and inherited cotton farms and systemic discrimination. Many years ago, North America won the war. Many who have read the history may insist that it was because of Abraham Lincoln. Nevertheless, what mattered was that the South Americans, with a good memory of the days of slavery, tired and broken due to the war, were now free. Without having to go to New York, slavery was now officially abolished. The reconstruction years after the war proceeded slow but were full of tensions. The project of deporting American black people to Africa had failed. So the black had to stay and find somewhere near the white and grey fields of cotton farms to coexist with their previous masters. The Southern masters, who were now obliged to share their homes, neighborhoods, and alleys with the poor, decided to protest against Washington's order in another way. Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation against blacks more prevalently in South America are a reminder of this period. All public and private services were divided into two sections, one for white people and one for second-grade citizens; that is, black people. A black man was not allowed to reach with his hand for a white man; they couldn't belong in the same position, so it didn't make sense for them to shake hands. Blacks and whites never had food next to each other, but if they somehow had to, whites had the priority. Black men and women had to wait for their previous masters. Titles were never assigned to black people. They were never allowed in white people's schools. Even in the most liberal song of The Beatles, you can't find a black man lighting a cigarette for a white woman.

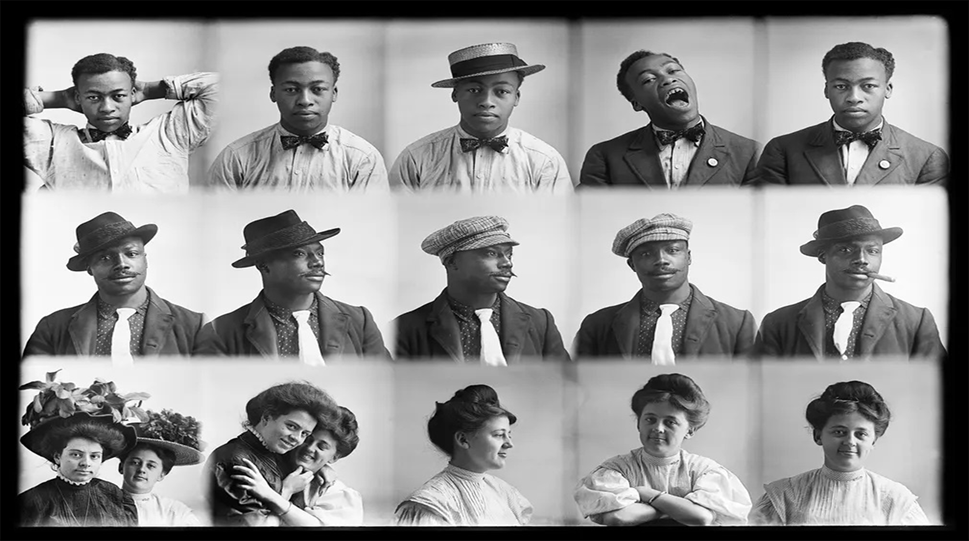

Hugh Mangum was born in the same period. He lived in South America, the heart of civil chaos, orders, and disorders. In the late 1890s, Mangum was an itinerant portraitist who took photographs of black and white men and women in North Carolina and Virginia. His vision was indifferent but curious. His portraits are reminders of a collective reality; for instance, the appearance of a colored customer indicates that the two races didn't have equal access to clothes. At the same time, these photographs extract something related to the subject's individuality. In Mangum's view, a black person was not bound to their social class. He tried to prove that although we should not beautify pain, we should note that there is life going on between the members of large and small communities; as much as we should care not to be deceived by numbness and otherness, we should avoid considering minorities passive as victims.

However, we cannot give Mangum full credit for this story. During the years of racial segregation, when a form of civil struggle was in progress to emphasize the presence of blacks, Mangum was working as a cheap photographer. Black people gave him one penny in return for an image of themselves to be left in history, hoping that it would help the next generations remember that they existed and were seen.

Nonetheless, Mangum didn't have much time to narrate history. He died when he was 44 years old. Years later, in 1970, the negatives were saved by a stranger just a few minutes before the cotton farm belonging to Mangum's family was destroyed. The negatives were then received by Duke University. This series of photos, displayed for the first time in Europe at the Photo Basel 2022, represents a section of US history during the racial segregation period.

Sources:

-

www.theguardian.com

-

www.en.wikipedia.org

-

www.kooness.com

-

www.archive.org

Cover and slider image:

- www.theguardian.com