Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam's Artwork in the Context of Art History

14 Aug 2022Original text in Farsi by Shamim Sabzevari

Translated to English by Sara Faezypour

Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam holds a unique position in Iran's modern art scene to the point of being celebrated as the "forerunner of Iran's modern art" for his creations and innovations. His articulated, mobile sculptures (1968 – 75) were outstanding examples of Iran's contemporary art. It is not an overstatement to say that his pieces are unparalleled in the art scene of Iran. During more than six decades of artistic activity, Vaziri Moghaddam was occupied with experimentation and exploration. Unlike many modern Iranian artists, he tried to create his language on par with contemporary currents instead of adapting Iranian artistic traditions to imitative modernistic approaches. To create these self-founded pieces, he eliminated any reference to the outer reality (be it Iranian or even non-Iranian). This correspondence to the contemporary art currents was what distinguished him from other artists of his time, reaching its peak with the creation of the articulated and mobile sculpture series which were completely eccentric and distinct in the art context of Iran at the time; this was natural as the art in Iran in that period did not have the means to understand and create such pieces, and the foundations for the conceptualization and making such artworks were not yet laid. But how did Vaziri Moghaddam come up with such an idea and put it into action? An idea that led to the creation of large sculptures with movable limbs, resembling a living organism that transforms and displays a giant monster.

In 1955, Vaziri Moghaddam moved to Italy, studying and creating artworks until 1964. He made some of his most famous pieces, known as the "Sand Paintings" in this period. After returning to Iran, he was kept away from painting for some time. Having no desire to continue the sand paintings, he did some line (the basic element of the sand compositions) exercises, leading, in a way, to geometrical abstract painting. These paintings set the scene for future three-dimensional construction experiences. Of course, the re-emergence of constructivist ideas and minimalist and op-art approaches in the first half of the 1960s played a significant role in his research and experimentations.

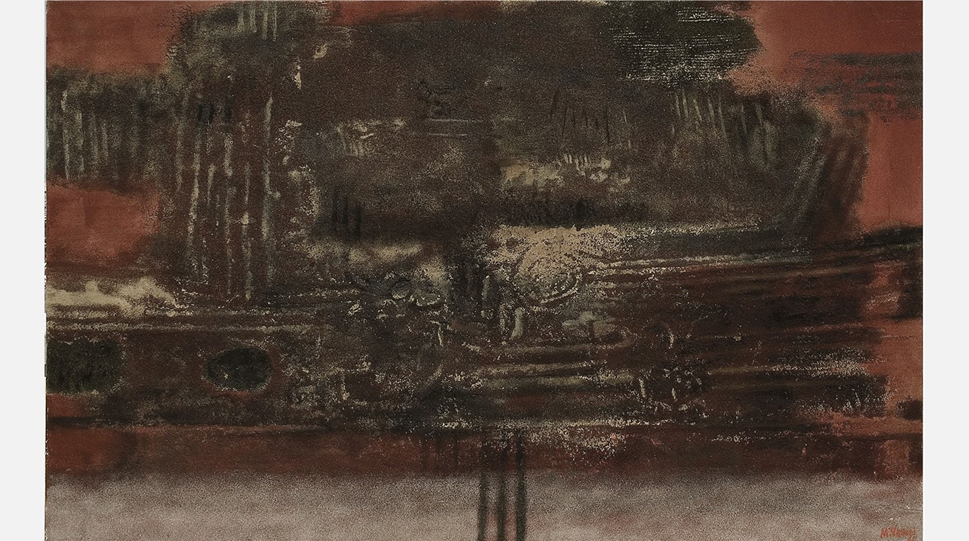

Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam | "Red and Black" | colored sand on canvas | 1961 | 115 ×185 cm

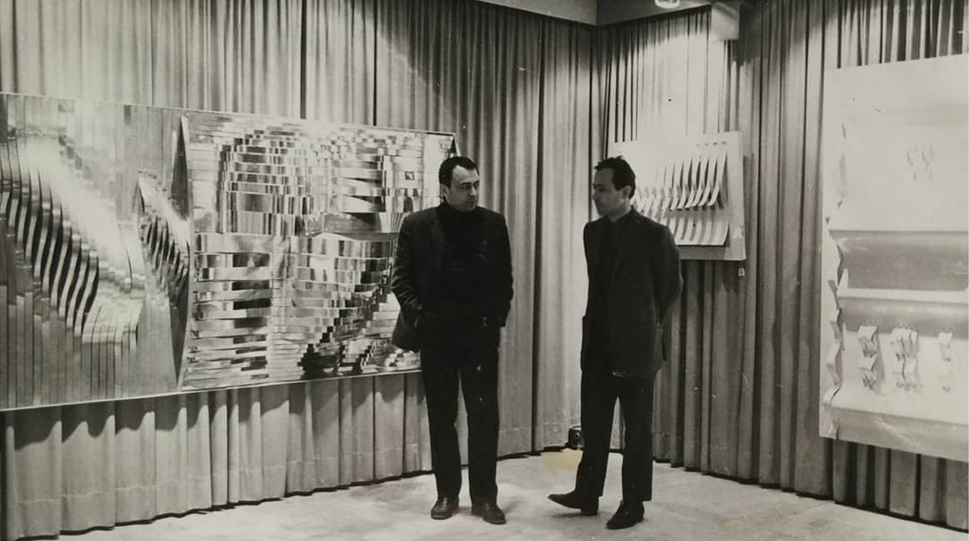

Moving on from the abstract painting period in the mid-60s, he shifted his focus on experiencing rhythm, line, and space with materials and other media. The outcome of this period was the relief collection made of cardboard, plastic, and aluminum that he displayed at Seyhoun Gallery in 1967. He later added color to these reliefs to intensify their visual dynamic: he painted the back of the metal strips, between which he placed pieces of colored wood. This game of light reflection on the raised and recessed forms created a manifestation of movement on the surface of the relief. In this period, Vaziri Moghaddam's main issue was the relationship between form and matter, with which he tried to experiment in different ways. The rhythm, movement, and optical illusion made it possible to transcend geometric abstraction in the aluminum reliefs. The third dimension used in the pieces went beyond the experience of creating two-dimensional paintings.

Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam | "Untitled" | aluminum, wood, and paint | 1968 | 200 x 200 x 15 cm

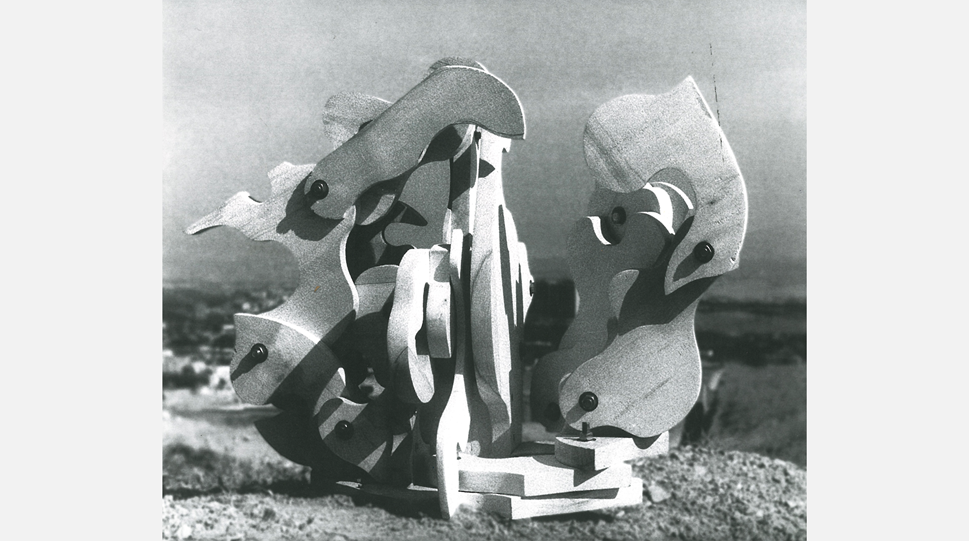

Entering the sphere of sculptural works, he started making abstract wood sculptures in 1968. Two approaches to volume can be examined in these works: firstly, making use of parallel strips with filled and hollow forms, following an almost definite structure, and their placement around a vertical axis, shaping the voluminal columns. In these pieces, the structured form of the reliefs can be traced in some way. In the second approach, the same vertical axis exists, but the abstract forms with different structures are detached from it from different directions; or maybe pieces are attached to form this vertical volume. Thus, the sculpture is shaped by the juxtaposition of negative and positive parts and the play of full and empty spaces. The hollow holes on the surface of the body or the curves created at the end of each part have as much to say as the positive surface of the body and its filled parts.

the scallop-like forms, created by cutting and eliminating wood, are evident both in the negative and recessed parts and the positive and bulging ones. This play with form and space is what distinguishes Vaziri Moghaddam from other Iranian artists. However, this idea cannot be particularly attributed to him. Long ago, cubist aesthetics had tried to open a new path in art expression, using lifelike and expressive forms. Jacques Lipchitz, one of the pioneers of cubist sculpting, attempted to create limb-like shapes with metaphorical characteristics by implementing holes and full and empty spaces in the center of the sculpture in 1920 (more than twenty years before Vaziri Moghaddam's experiments). Moreover, Constantin Brâncuși, another renowned and eminent artist, challenged the figurative sculpture tradition with his simple and back-and-forth-going forms, and created all-encompassing yet simple sculptures, utilizing different styles and materials. This process of creating sculptures was carried on by numerous artists.

However, the main transformation in his work happened in 1969, after his one-year residency in The Cité Internationale des Arts. After completing this period and returning to Iran, he began building his articulated and mobile sculptures. As he said himself,

"In 1969, I started making wooden sculptures using metal reliefs. I abandoned the metal strips, basing my work on the wooden slices between them. At first, the wooden pieces were attached at 90-degree angles. Sometimes pure wood, and other times, painted ones with arches and holes, the logical transformation of these motionless sculptures led me to build articulated ones. At the end of 1969, instead of gluing the wooden pieces together, I connected them with nuts and bolts, and like the joints of the human body, I made it possible for them to open and close."

Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam | "Scuffle" | wood | 1973 | Collection of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art

In his articulated and mobile sculpture, two concerns can be detected: the first is the topic of "movement" and the second is the "viewer's participation". As he said so himself,

"Here the issue was the form leaving its fixed and imposed state and the audience being able to create a new form at any moment. In other words, test his or her mental quality in shaping the pieces. This relief placed in an architectural space does not occupy space but constantly enables the space to change."

Vaziri Moghaddam's wooden sculptures with jagged edges on one hand, and curved forms on the other hand, simultaneously attract and repel the audience. The viewer could stack up all its parts in one corner or spread all the limbs throughout its whole body, or even leave some of them closed or open. Here the audience can choose and decide, that is why the space is constantly changing and diversifying. In other words, the artist has made a form and presented it to the viewer to create his new forms and participate in the creative moment.

As a result, the tradition of modernism, which requires the obliged passivity of the viewer toward the works, is broken in these sculptures and the audience takes part in the process of creation, performance, and making of the art piece, challenging it in some way. This work was not only unique and unprecedented in the Iranian art scene, but also the idea of employing movement in sculptures was far from Iran's art current, but cannot be considered the result of the development of such a process and the experiences of the Iranian sculptor artists. In an interview in 2013, Vaziri Moghaddam considered the initial idea of creating these works to be by "chance" or "coincidence" as well, considering the whole process as spontaneous and improvised.

"One day something happened; to make a hole in one wood piece, I placed other pieces under it, and turned on the drill. As I was pressing the drill downwards, the top wood piece began spinning around itself. This made me think that if I passed a piece of iron through these holes, these forms can move on top of each other."

Although this account may be true of how the idea of the articulated and mobile sculptures was generated, the whole process cannot be reduced to it. About four decades before this interview, just when he was at the heart of creating the articulated and mobile works, Vaziri Moghaddam had narrated the started point of the process differently, speaking of a kind of "necessity".

"I never like sculptures that remain silent in one place. I was in dire need of a device that could be closed in one point like the human arm and opened whenever it wanted, and take root in all parts" (Iran Zamin Youth Newspaper, 1974)

Here he considered the creation of articulated sculptures as a response to a sort of need. Comparing and contrasting these two narratives helps us have a more accurate perception of the real story. It seems that Vaziri Moghaddam recognized a necessity to change the making of still sculptures, and came up with the idea of implementing this necessity after the accident in his workshop. From a logical point of view, a mere unconscious spark cannot be considered the primary source of the creation of such artworks in the art current as the ideas and activities of an artist are not separated from the social and cultural context of his or her life. The artist does not create artworks in a vacuum. The proposition of believing in the ingenuity of an artist would lead to misconceptions and inadequate analysis if his or her growth and development background are dismissed, especially considering that in those days Vaziri Moghaddam found himself in a context, the confrontation, and familiarization of which facilitated the change of his artistic approach.

Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam | From the articulated sculpture series | "Untitled" | wood and metal | 1970

A study of history and art movements shows that decades before these experimentations by Vaziri Moghaddam, many attempts were made in western modernism to introduce the notion of movement in artworks. Also contemporary to his time and parallel to his activities another type of movement art (kinetic art) was introduced. Finding its way into the modern art movement more or less in the first decade of the 20th century, kinetic art did not mean a mobile sculpture in an environment but served as a transformation and network of connections, defining the structure concerning time and place. Here, the art piece is not a rigid body but an object that identifies its meaning in connection with the audience. In 1909, futurist artists established a new aesthetics, emphasizing speed and movement. Using multiplicity and segmentation in painting and sculpture, they tried to create artworks that appeared to be a mixture of close and far, moving and still objects; an art that is alive and racing. This idea has turned into one of the most important issues in the art world ever since. The main idea of kinetic art is to challenge the stasis and stability of the shapes and two-dimensional and three-dimensional combinations. The moving parts of these works were usually put in motion by wind power, mechanical tools, hand force, electrical engines, or batteries. Many artists began experimenting in this area in the first decades of the 20th century. A constructivist artist like Vladimir Tatlin built suspending sculptures in the air, evoking a sense of movement. Aleksandr Rodchenko created hanging constructions. In 1920, Naum Gabo made mobile sculptures equipped with an electrical engine. Alberto Giacometti was one of the surrealists that experienced building moving objects. From the 1940s to the 1960s, Alexander Calder's name and his "mobiles" were associated with Kinetic art and Yaacov Agam became one of the pioneers of Kinetic and Op art during the 1950s and 1960s.

Moreover, there is the issue of the viewer's interaction in producing movement and transforming the structure of the sculpture. Since the first decades of the 20th century, numerous artists and theorists sought to blur the line between the author and the audience, and involve the latter in the formation, performance, and alteration of art. These concerns, beginning with the futurists' soirees and group meetings, developed with Dadaists' and Surrealists' exhibitions, culminating during the 60s and 70s; meaning the time when modernist traditions were being dismantled and the emphasis on the role of the artist was losing its importance. During this period, the audience's participation in the artist's performance plan and the bond between art and society turned into one of the main features of art, manifested in the art of "Happening" and the productions of the "Fluxus" movement. This was the grand objective of Postmodernism.

As previously stated, these ideas and such great transformation in Vaziri Moghaddam's work happened after his trip to France and residing there. A brief overview of the artistic events of the West, especially France, at the time Vaziri Moghaddam was living there, meaning the end of the 60s, provides us with a better and more accurate perspective. During the 50s and 60s, the followers of Neo-realist and Op art were able to make major changes in the French art scene. For example, the school of "Neo-realism in Paris" was itself a branch of an international movement known as the "New Tendency", having quite diverse formations. Implementing new materials and techniques of science and industry, group activity approaches, integrating the effects of light and sound, and breaking aesthetic standards were considered its key characteristics. The French branch of this tendency, working as the "GRAV", paid special attention to visual phenomena and the notion of perception and contemplation with a scientific view, in other words, they rejected the separation between art creation and the public. For these artists, the passivity of the audience when faced with an artwork and the imposed acceptance of what is counted as art was not approved. They believed that the audience was able to understand and react to the artwork and considered a work valuable when it spurred the viewer into action and created an environment of communication and engagement. Thus, the experience of creation, and the significance of the creator are lost in the process and the audience is encouraged to take part. Involving the viewers and refusing their passivity to discredit the artist's position, the group removed its activities from traditional galleries, remaining in close contact with the public and audience as much as possible.

With the activities of these neorealists in the 60s in France, other artists with various styles of Kinetic art were creating artworks at the same time. For example, Yaacov Agam, known at that time as one of the forerunners of Kinetic art, moved to France. A significant feature in Agam's work, which he called "trap art", was that they could be manipulated. Having no predetermined structure, these works consisted of movable parts, provoking the viewer to play by actively engaging them. Inspired by Calder's work, another artist called Pol Bury focused on making a piece at that time, titled, "Mobile Surfaces", in which he provided the opportunity for the audience to directly participate and be able to change its composition. Concentrating on the connection between art and technology, Nicolas Shöffer and Francis Tierney were other active artists in Paris, creating kinetic artworks. Additionally, Brazilian artist, Lygia Clark, who was studying art in Paris during the 50s, created works that seemed, above all, like living organisms, focusing on space, time, movement, and matter.

This brief overview of the artistic context influencing Vaziri Moghaddam better shows the groundbreaking position of the artist in Iran's modern art scene and stresses his explorer and empirical spirit. Having resided in Italy from 1955 for a time, he went to Paris in 1968 and was influenced by the contemporary art currents. Instead of reproducing traditional art, or combining Iranian art with copied versions of western modern art, he created artworks that had a lot to say in the international arena of the day. Rather than appeasing the tastes of organizations, galleries, or art markets in Iran, he preferred to pursue what he had learned and experienced, and experiment instead of treading water and repeating. For this reason, at a time when Iranian sculptors still did not grasp many aspects of the modern art movement, he began to create works that were cutting edge in the world. Utilizing the different features of the kinetic-interactive art, involving the audience directly in the artwork, the experience of making or performing it, he created his articulated sculptures. It is only natural that these sculptures were considered odd pieces in the context of Iranian art as they belonged to another artistic ground.

Consequently, the progressive form and content of these sculptures not only challenged the power relations in society and art policies, but also the internal art relations between the artist and the audience. This process cast doubt on the position of the artist (author) as the main creator and determinant of art and as a result, the audience was able to participate in the creation and formation procedure of the artwork, applying their inner thoughts as well as gaining a different understanding of an art piece. this approach allows for different readings of an art piece in which the lived experience, perspective, and manner of thinking of each person about this three-dimensional object, when faced with it, as well as the space and form it occupies are influential. Naturally, here the audience's critique of the artwork and transfer of meaning is possible not through the content but the form. This is the masterpiece of Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam, distinguishing and eternalizing his position in Iranian modern art and connecting him with the art world.

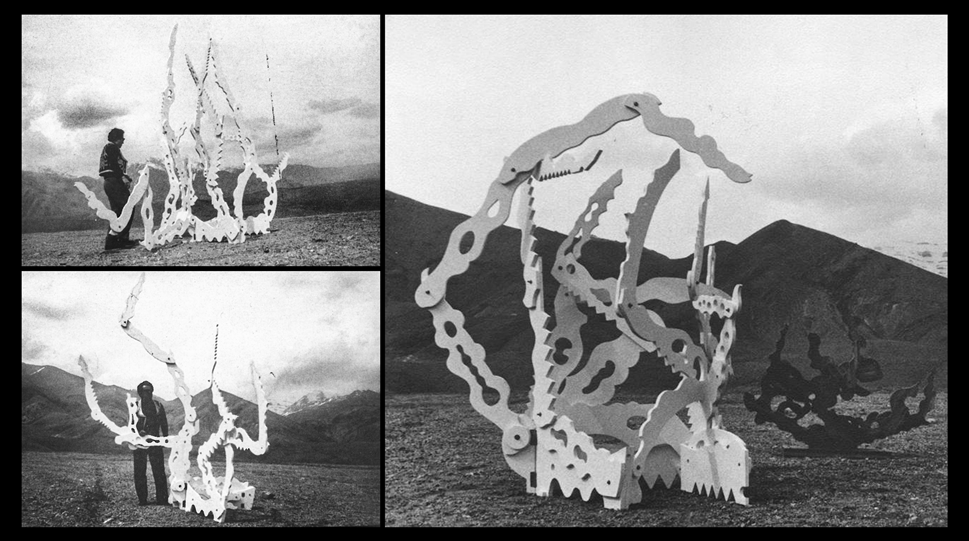

Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam | "Metamorphism of Form" | white painted wood | 1970 | vertically and horizontally expandable | 41 pieces

Image 1: Mohsen Vaziri Moghddam, "Metamorphism of Form", white painted wood, 1970, vertically and horizontally expandable

Image 2: Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam, his show at Seyhoun Gallery, 1967

Image 3: Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam, "Growth", painted wood, 1968, 110 cm in height, from the artist's personal collection

Image 4: Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam, "Organic Forms" (articulated sculptures), wood, 1969, from the artist's personal collection