Interview with Alfred Yaghoubzadeh, Photographer

05 Mar 2022Kargozaran Newspaper | Sunday, February 10, 2008

I Wouldn't Be a Photographer If It Wasn't for the Iranian Revolution

By the outbreak of mass rallies in the fall and winter of 1979, Alfred Yaghoubzadeh quits university to start his journey of photography with his camera. His records of the U.S. Embassy capture and the Iraq war against Iran elevates him into a professional photographer. Photographing dozens of world leaders, several revolutions and wars, and collaborating with international magazines such as New York Stern, Paris Match, Sipa Press, Sygma, etc. are all in his records. The 49 years old jury of the World Press Festival and the winner of the American Overseas Awards, French Angers Awards, and World Press Prize has now decided to return to Iran a few days after his birthday on February 3. After 24 years of being away from this country, now he wants to come back to Iran with his wife and three sons. On the anniversary of the 1979 Revolution, we talked with him from the very first days of his photography career to the present day.

Let's go back to the first days when you started photographing – By the way, how many years have you been away from Iran?

24 years. First, I went to Delhi from Tehran, stayed there for three months, and then I went to Paris. India had a different atmosphere from Iran.

In what sense?

Their color, their religion, their living environment, etc.; everything was different. There was a war in Iran at that time and life is different during wartime.

Let’s go back to the first days of your photography...

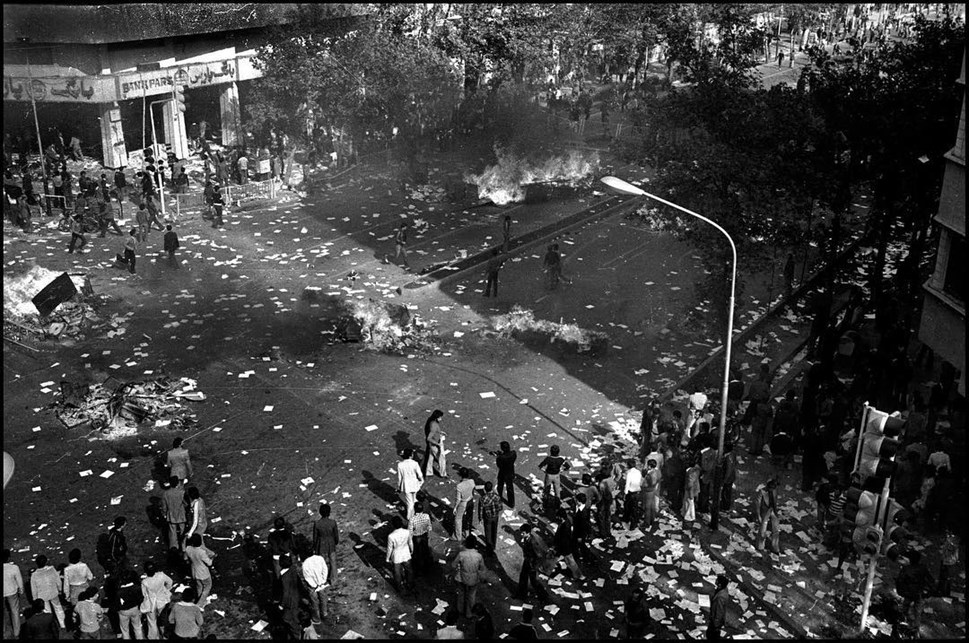

Before the Revolution, I was studying interior architecture at the Faculty of Fine Arts. The revolution happened at the same time, I had no idea about it. I didn't know what the revolution mean. We had the White Revolution in our textbooks, but I didn't even know the meaning of that one too. So, the protests escalated gradually and people took the control of streets; the Pahlavi Dynasty collapsed and the Islamic Republic won. I started photographing at that time, and it was like a new photography course that started along with interior architecture. When the demonstrations became intense, I bought a camera and it felt like I was learning photography at a new school. I should also mention the support and guidance of Asghar Bichareh; our only photographer neighbor.

Were your first frames of the people's protests?

Yes.

What was interesting in these demonstrations? Only because it was the first time you were attracted to it or was there another reason that you bought a camera for?

When I went to the demonstration for the first time, I suddenly found myself between the crowd raising my fist and saying "Down with the Shah". Then I realized I didn't know how to do it at all. Coincidentally, during demonstrations and shootings, I saw some photographers and their cameras caught my eyes. By then, I knew the best demonstration for me was to take pictures and give useful information to people. It was better than chanting. Day by day, I was aware of the details of the protests, and I slowly became addicted to photography.

Didn't those photos get published anywhere?

No, because I was learning and they were so basic. I still have them and I give them a zero. By the end of the Revolution, it was like I was graduated in photography from high school. The second level for me was during the U.S. Embassy capture. At that time, I was better technically and well equipped and I was even more familiar with the photo presentation in terms of quality and framing. I used to commute to the embassy frequently and after that, the Iraq-Iran war began. During the war, I got myself to the battlefront for the first time. I had no clue about war. I went to Khorramshahr by any means. There were bombardments and missiles, also everyone had guns. I had seen war in movies, but at that time I found myself in the middle of the war. There was danger, even during the days of the Revolution, but I was excited. I didn't know what was going on. The crowd was pushing you forward. In short, I stayed for a few days and returned back to Tehran. In Tehran, I told myself that it is a war, not a joke, if you become afraid and give up, you will be killed or failed. I decided to take care of myself and take photographs at any price. Once again, I went to the battlefront without any support or even a journalist card. The war had become worse. I photographed three years of war. Something came by accident; due to commander Chamran's passion for photography, I once took the opportunity to introduce myself to him. He liked photography and supported me completely to photograph the war. He trusted me and I stayed with them for three years in the southern regions. At the same time, Banisadr was there, his headquarters was in Ahvaz and I was often commuting there, this made them know me and I was able to get into the army. I got acquainted with General Valiollah Fallahi; he helped me to go further to the frontline to take part in attacks. I returned to Tehran after Dr. Chamran and Valiollah Fallahi were martyred, as it became harder for me to work and stay in the war zones; they were my only supporters. At that time, The Conference of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was held in India and I was sent there to photograph the event by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance.

How did the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance know you?

From Iran's War Propaganda Headquarters. Of course, I was not a member and they did not accept me as I was working with the foreign press.

Where did you work with?

I worked with the Gamma Agency in France. There was a sense of distrust of us, those who were working with the foreign media and press. My job was photography and I wasn't affiliated with any party. I also worked as a freelance photographer with Gamma. At the time, my country was engaged in war and I wanted to serve my country. Our job was appreciated by some and undervalued by others. The Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance was helpful and we were creating books, posters, and organizing shows from war photographs to show the world what is going on in Iran. There were four of us making portable posters; Mohammad Farnoud, Kaveh Golestan, and Manoocher Deghati. I spent a lot of time on the battlefront, the first time I stayed for nine months and didn't go home. The transportation was difficult and the front felt like home to me. When I went back, I developed my photos and shared them with the Gamma Agency and the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. I had some cooperation with the Mizan newspaper as well. During the capture of the US embassy, I worked with the Associated Press as a freelance photographer. At that time, it was as if I had become a professional, but the experience of revolution and war shocked me. I witnessed very disturbing scenes and I admitted that the revolution and war include these aspects too. In these experiences, I saw death in front of my eyes.

What happened in India?

When I was in India, Gamma Agency offered to send me to other parts of the world where revolutions were taking place: Lebanon, El Salvador, Nicaragua, etc. There was a war in El Salvador. In 1978, the earth seemed to have been separated into two parts: east and west. Nicaragua was left-communist, and El Salvador was right-American. For instance, Pakistani and American. In Afghanistan, some Afghan forces were helped and...

Almost the same period when the Warsaw Pact and NATO were facing each other...

Exactly. These kinds of news were everywhere; the Eastern Bloc facing the Western Bloc. When I got an offer from Gamma Agency, I thought that the sky is always blue everywhere, but it was better to go and see other parts of the world to gain new experiences. After India, I went to France. Then I stayed in Nicaragua for a few weeks. Again, everything was different there: language, culture, system, etc. I went back to France and then to Lebanon, in 1982 and 1983 the condition was bad there. I stayed in Lebanon for three years. I was taking pictures for the Gamma Agency until 1983, however, after some financial issues, I quit.

For example, my salary was not much for photographing in Lebanon. The price of a bottle of water was $10 and the cost of a hotel room was $300-400. The Gamma Agency gave me a one-way ticket to Lebanon and the money ran out in a few days. I had to eat dry bread. Then, my job with the Sygma Agency began; it was a rival for Gamma. I cooperated with them for a year and then I started working with Sipa; from late 1984 till now.

Kaveh Golestan was martyred while photographing these very revolutions and wars. Did you ever think that his fate would happen to you?

If you think about this, it happens to you and you will give up. You shouldn't think about it.

Among you four – Farnoud, Golestan, Deghati, and you – were there ever talks of death during the photography?

No, every time I went to photograph the war, for example, photographing the Iraq-Iran war, I used to tell myself, "I made a mistake, let it be the last time." There were moments when I thought I was dead. I spent time with the warriors who all became martyrs. When the bombardments were too much, I used to tell myself that if I get out of this situation, I wouldn't take pictures anymore. Again, two hours later, I was going back for photography. There were moments when I told myself I was wrong, but I never thought about death. As I mentioned when I first went to Khorramshahr, I promised myself not to be afraid. That's the war, one has to go till the end. I was injured twice with grenades and shrapnel in Lebanon. Many people around me were killed, nevertheless, when I had crutches and was injured, I continued running and taking pictures. If you think too much about death, you will lose control soon. Death comes spontaneously, it doesn't alert. So, you have to fight with it. I was injured in Chechnya a few years ago and was in a bad situation, I had to spend about 10 or 11 months between home and hospital to heal.

Even when this happened to Kaveh Golestan, didn't this concern you?

No, apart from Kaveh, I had many other friends who were killed; in Nicaragua, in Iranian Revolution. I had a friend in Nicaragua; Olivier Ryu, he was shot in the armpits and was killed by El Salvadorian forces. There was an American Newsweek photographer called John Hoagland, he also was killed in Lebanon. I remember once in Lebanon, I was photographing in a parking lot, just as I came out for smoking, bombings began. The ball hit this parking lot and then everyone died. There were some of my colleagues there, Adnan, George, etc. It wasn't just about my friends or colleagues, there were civilians and strangers who ended up dead in these wars and it was hard to bear. I'm an uninvited guest to the places I go. They can welcome me or beat and take me captive. There are always more casualties and problems of war for the people of that country. So, I'm an uninvited guest, my life doesn't mean anything to anyone in that place. Accidents can hit me at any time and I shouldn't think about it. It's better not to ask myself these questions. In Khorramshahr, I promised myself, to leave my life to time and destiny. I share a memory: after the deportation of Benazir Bhutto when she arrived in Pakistan, I was accompanying her from the morning until a few moments before the incident. While photographing, something took me away for a moment, I walked away and the car exploded. I saw a car bringing the assailant, I asked myself why they had let him come so close; I was 20 meters away from the car at the time of explosion. That is why I won't even decide to be afraid or think about my death. It's destiny.

Whether you've gone to photograph revolutions and wars in several countries was in consequence of starting photography with the Iranian Revolution and the Iraq-Iran War, or are there other reasons?

As I mentioned, I was busy with fine arts, sculpture, architecture, painting, etc. I had no idea about the war. The only thing I knew was on TV; cowboy movies, pistols, and shooting. Well, it wasn't even the Vietnam War movies as they were made after the war. But, it seems that I have a distant acquaintance with revolution and war through my family.

My grandmother came to Iran from Russia after the Lenin Revolution. My mother's family was massacred by the Ottomans and came to Iran. My father came from the Turkish border after a series of massacres. In short, maybe if it wasn't for the revolution, I wouldn't be a photographer. I consider myself indebted to the Iranian Revolution. The war was along with the same category. As I was familiar with this process, I followed a few more wars and revolutions as well. Time passed and I tried to make myself interested in other subjects. I told myself this world is not just about war.

This world is like a rainbow, if you see just red, you will get tired. Other colors should be looked at. It still goes on; sports, fashion, documentary stories, and everything in life. The only issue I don't like is being a paparazzi. I do not want to be a spoilsport. It's good money, but in some way, I have to give back the money I earned over the years from the issues of people's lives.

I see myself unbiased in wars. In the meanwhile, I have tried to take the weak side and I try to do my best to be the voice of the side that is being oppressed.

I'm not on anyone's payroll. The weak side has weapons, money, and helps as well. I'm just trying to get the oppressed voice out. This is also a part of photojournalism. Recently, I'd like to address all the subjects. Our life is short, the world is beautiful. Why should I just stick to war?

When and where was your last war photography?

Lebanon's 33-day war.

Didn't you tell yourself that war photography is enough?

I told myself, but sometimes it's like adrenaline and drugs. I like to be there and see my friends. I don't wish for a war to happen. I wouldn't put my camera away just because of the war.

I went to the World Cup in Germany. I went to the 60th anniversary of the U.S. defeat in the Vietnam War and I made a picture report there; from children who were paralyzed and other crimes. It's been four generations now and there are still incomplete births there. Well, I photograph religious rituals as well and I do not put a limit on myself. Recently, after many years, I have been able to come to Iran frequently and follow the dream subjects of my old times. I'm glad I've been able to go through my favorite subjects that have been with me in the past.

This is an English translation from the original Persian text.