Akram Ahmadi Tavana In conversation with Mojtaba Amini

24 Sep 2023Mojtaba Amini is an artist who depicts the realities of our times, albeit in a veiled, indirect manner. By flipping through these pages, and reviewing his work from the past decade, one can survey a selective, particular interpretation of certain instances in the political history of regions in conflict. His obscure presentation is intended to attract the viewer’s attention to a certain location, but in this presentation the main subject matter is excised, and what remains is a hardly decipherable, vague trace of an event or person. As such viewers don’t observe Amini’s work, rather they experience a process of discovery leading to an uncertain degree of understanding.

Mojtaba Amini’s main subject matter is the fundamental mystery faced by humankind: the subject of death. He has escaped death in silence and bitterness, but has never been set free from it. The artist’s dark, course pieces present the viewer with a world of pain and anxiety, while at the same time providing solace to their creator. His escape from death has seeped its way into the work’s concept and material, influencing its shape and form, and continuing into the viewer’s world. Amini conceptualizes death by using decomposable material and challenging the permanence of his work. For him death does not happen in an instance but is a gradual process. In Amini’s pieces death is neither an end nor a release, it is not a moment of grief or happiness, it isn’t bitter or sweet; it is merely an unknown, unavoidable fact. Amini uses hues in the Arabic titles of his works about death (“almawt al'ahmar” or Red Death), but the work itself is often done in dark tones. He is interested in types of death that reinterpret or recreate certain concepts and definitions for the living.

In order to understand Mojtaba Amini’s work, one needs to be familiar with the artist and his portfolio. Sometimes his thought process and the concepts that arise from it, result in a single piece, but each piece ends up being part of a whole. And it is in this relationship to the whole that the work finds meaning. The artist directs the viewer to the inspiration behind each piece, as well as the various symbolism contained within them.

This conversation is intended to help the viewer discover hidden layers within Amini’s work, and to see them for a few moments from the artist’s perspective.

Language is a complex and mysterious source of amusement for Amini, one that he uses both as inspiration, and as a means of expression, albeit an ambiguous, meandering expression that for the viewer is often a hindrance rather than clarification. He chooses the Arabic language – something his is familiar with and has been exposed to – in order to widen the range of his questions. Layers of complexity get added on, to the point that the initial concept becomes obscure. The artist intentionally makes the viewer struggle. Amini uses language in a variety of ways: as his main subject matter, as text used within the work, and also as titles for his pieces. He includes complicated references, de-familiarizes words (by using archaic and unfamiliar definitions of familiar words), and homogenizes the form and content of text.

Mojtaba Amini finds his subject matter in unspecific geographies. The repetition and depth of events in these regions is insanely accelerated, making the recording, and even the experience and understanding of these events, very difficult. He chooses an event and empathizes with it, and then he gives it form within the overall body of his work, before finally sharing it with his viewers. In fact from among a multitude of events/subjects, the artist directs a distraught public to a place beyond the event itself, forcing them to think. From Syrian refugees to Iranian workers, these are things that have an impact on Amini and lead him to express their lives and deaths, presenting the viewer with an historical awareness.

Experimenting with different media is like an intellectual/healing process for the artist, and leads to a certain level of physicality between the artist and his creations. Amini has the essential and sensitive ability to select a unique medium and form of expression in order to convey his concept in the most complete manner. His choice of material and they way he works with it, leads to a particular quality that may not provide answers to his questions, but is inline with their meaning. There is a similar lack of certainty in the content, material, and ultimate form of the work. For Amini material contains both history and meaning; this is why he uses remnants from animals such as wool, fat, and animal glue, to create (and sometimes destroy).

Mojtaba Amini takes the viewer out of the world of art and into concepts rooted in violence, such as social protest, revolution, child execution, self-immolation, rape, and the immigration and death of refugees. In order to answer questions, he ends up posing broader topics. He candidly shares his past, memories, fears, and personal and social concerns with the viewer, and the work that is created in the process is a piece of art that belongs to its time, carrying the stench of ugliness and pain.

Interview between Mojtaba Amini and Akram Ahmadi -Tavana :

Tavana _ One can approach every one of your pieces (regardless of their subject matter) using the keyword "death".

Amini _ This is rooted in my past, in the death of my grandfather. He was a person I really loved and his death was difficult for me. He spent a long time in his deathbed, suffered from bedsores, and finally passed away. It was the first time I lost someone close to me. There were a lot of stories surrounding his life and death. I was in my teenage years and the experience has affected me up to the present time. Later I came face-to-face with death and it highlighted the concept even more for me. My closeness to my grandfather, and the time I spent as a child living in a desert village in Sabzevar, forms the basis of many of my pieces. My use of animal skins, wool, soap, and charcoal comes from the experience of living in this difficult, desert region.

Tavana _ You referred to some of the material you use, things that are in a way related to death. Is your process of creating a work of art also tied to the concept of death?

Yes, when I smell the stench of decomposing material in the work.

Tavana _ In your 2012 exhibition at Aaran Gallery (“Talqin” or Instructing the Dead), you focused on the subject of death. What made you present your psychological therapy – something so private – in such a public manner?

The further I go the more I am influenced by that exhibition; it keeps leading to new things in my work. I experienced an event in 2010 that brought my close to death at a time when I was thirty-years-old, with a young, healthy body. My muscles and heartbeat would suddenly change, and I’d have a panic attack and couldn’t move. I suffered from this condition for several years, and anti-depressants made it worse. In those years I witnessed many of my friends losing their lives to addiction.

For that exhibition I made my own body using white soap, and presented its decay, disability, and ultimate death. I roared that death is being instructed. I included other signs so the viewer could find some things in common with me. The situation we experienced in those days, our utter sense of hopelessness, was suffocating us and influencing our behavior.

Tavana _ What sorts of signs did you include?

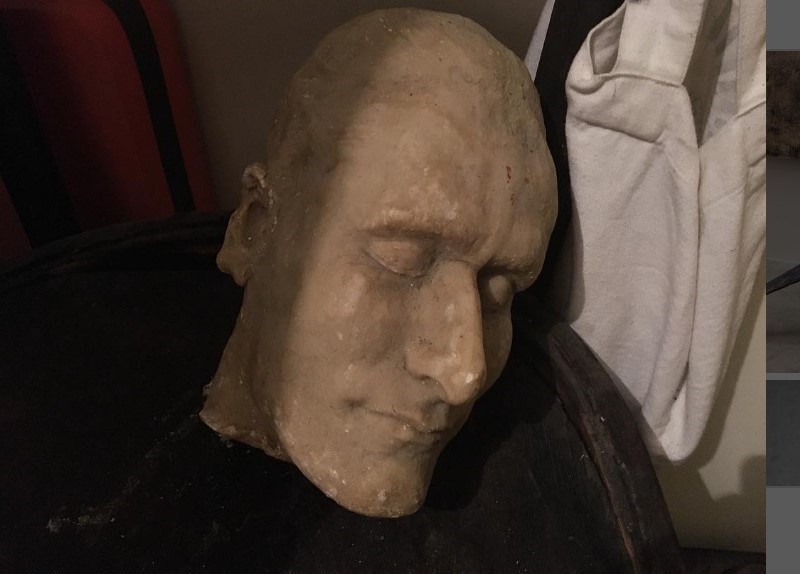

There were many different signs and symbols. In the death masks I used titles from Käthe Kollwitz’s best-known works, pieces that make direct references to the terrifying time of the artist’s life. I brought their fear and terror into my own work; titles like “Death of the Kneeling Girl”, “Death Shroud”, and “Death as Friend”. Using white soap I made masks of my wife’s face and my own, and used these titles for the masks that went through the process of decay. I placed a piece of camphor next to each mask. During that time I’d put camphor next to each piece I’d make. Camphor is often placed in the underarm of a corpse in order to cover up its stench. The sharp scent of camphor, lead, and wool were symbols of death; a personal narrative tied to social issues. As Shamlou eloquently puts it, “They scare us of death, as if we are alive!”

Tavana _ Some of your pieces indicate a figure in the process of dying (I am referring to sculptures you've made out of camel fat). They go through the process of decay but the viewer does not have the opportunity to witness this to its conclusion. Is this on purpose? Do you care about their ultimate shape and form?

It is not on purpose. These pieces were exhibited at Aaran Gallery for a short time, and even in that short period they showed signs of decay and decomposition. The process of decay that I had in mind would take several months. After the exhibition I decided not to record this process through photographs, because the act of recording would prevent it from “dying”, which was against my intention. Later I gave their remnants to another artist to use in a sculpture, but it didn’t work out. Eventually I brought them back to the studio and wrapped them up. I placed the carcass on a bed and under its head I wrote “Talqin” in Thuluth script. This became the basis of some collages that I still continue to make; box like beds that have swallowed the corpse.

Mojtaba Amini is an artist who depicts the realities of our times, albeit in a veiled, indirect manner. By flipping through these pages, and reviewing his work from the past decade, one can survey a selective, particular interpretation of certain instances in the political history of regions in conflict. His obscure presentation is intended to attract the viewer’s attention to a certain location, but in this presentation the main subject matter is excised, and what remains is a hardly decipherable, vague trace of an event or person. As such viewers don’t observe Amini’s work, rather they experience a process of discovery leading to an uncertain degree of understanding.

Mojtaba Amini’s main subject matter is the fundamental mystery faced by humankind: the subject of death. He has escaped death in silence and bitterness, but has never been set free from it. The artist’s dark, course pieces present the viewer with a world of pain and anxiety, while at the same time providing solace to their creator. His escape from death has seeped its way into the work’s concept and material, influencing its shape and form, and continuing into the viewer’s world. Amini conceptualizes death by using decomposable material and challenging the permanence of his work. For him death does not happen in an instance but is a gradual process. In Amini’s pieces death is neither an end nor a release, it is not a moment of grief or happiness, it isn’t bitter or sweet; it is merely an unknown, unavoidable fact. Amini uses hues in the Arabic titles of his works about death (“almawt al'ahmar” or Red Death), but the work itself is often done in dark tones. He is interested in types of death that reinterpret or recreate certain concepts and definitions for the living.

In order to understand Mojtaba Amini’s work, one needs to be familiar with the artist and his portfolio. Sometimes his thought process and the concepts that arise from it, result in a single piece, but each piece ends up being part of a whole. And it is in this relationship to the whole that the work finds meaning. The artist directs the viewer to the inspiration behind each piece, as well as the various symbolism contained within them.

This conversation is intended to help the viewer discover hidden layers within Amini’s work, and to see them for a few moments from the artist’s perspective.

Language is a complex and mysterious source of amusement for Amini, one that he uses both as inspiration, and as a means of expression, albeit an ambiguous, meandering expression that for the viewer is often a hindrance rather than clarification. He chooses the Arabic language – something his is familiar with and has been exposed to – in order to widen the range of his questions. Layers of complexity get added on, to the point that the initial concept becomes obscure. The artist intentionally makes the viewer struggle. Amini uses language in a variety of ways: as his main subject matter, as text used within the work, and also as titles for his pieces. He includes complicated references, de-familiarizes words (by using archaic and unfamiliar definitions of familiar words), and homogenizes the form and content of text.

Mojtaba Amini finds his subject matter in unspecific geographies. The repetition and depth of events in these regions is insanely accelerated, making the recording, and even the experience and understanding of these events, very difficult. He chooses an event and empathizes with it, and then he gives it form within the overall body of his work, before finally sharing it with his viewers. In fact from among a multitude of events/subjects, the artist directs a distraught public to a place beyond the event itself, forcing them to think. From Syrian refugees to Iranian workers, these are things that have an impact on Amini and lead him to express their lives and deaths, presenting the viewer with an historical awareness.

Experimenting with different media is like an intellectual/healing process for the artist, and leads to a certain level of physicality between the artist and his creations. Amini has the essential and sensitive ability to select a unique medium and form of expression in order to convey his concept in the most complete manner. His choice of material and they way he works with it, leads to a particular quality that may not provide answers to his questions, but is inline with their meaning. There is a similar lack of certainty in the content, material, and ultimate form of the work. For Amini material contains both history and meaning; this is why he uses remnants from animals such as wool, fat, and animal glue, to create (and sometimes destroy).

Mojtaba Amini takes the viewer out of the world of art and into concepts rooted in violence, such as social protest, revolution, child execution, self-immolation, rape, and the immigration and death of refugees. In order to answer questions, he ends up posing broader topics. He candidly shares his past, memories, fears, and personal and social concerns with the viewer, and the work that is created in the process is a piece of art that belongs to its time, carrying the stench of ugliness and pain.

Tavana _ The first solo exhibition you had was titled “Children Program” and was held at Golestan Gallery in 2010. Talk about this installation.

I covered the gallery’s walls in wallpaper to make it look like a house. I made small hejles using mirrors, and made portraits of children in frames that looked like a hejle. These memorials are usually placed outside on the street to inform passersby that someone has died there. One of the children I made a portrait of had an exhibition at Golestan Gallery a few years before I did. I didn’t intend this as a mere exhibition, but as I mentioned above, it didn’t turn out exactly as I had intended.

Tavana _ The topic of death was bold in that exhibition too, but your critical gaze was focused on the right to live. The title “Children Program” highlighted this paradox. How did the frank form of expressing political/social issues in your first exhibition, give its place so quickly to the complicated, multi-layered quality of your later works?

As I mentioned before, my intention here was not merely to have an exhibition. I wanted to create a situation where we could gain the approval of victim’s families (to prevent the execution of perpetrators who had been sentenced to death). I used the title “Children Program” because the law surrounding this issue is very complicated. The Iranian justice system has attempted to come up with ways to avoid the implementation of the law (execution), and to gain the forgiveness of victims’ families.

My later series lent themselves to being expressed in multiple layers, such as the death of refugees and other similar topics.

Tavana _ The work you have created over the years shows your sensitivity to political and social events, whether in Iran or other countries. What draws you to these subjects?

Many people have similar sensitivities, whether they directly bring them into their work or not. My social/political ideology was formed during my time at Tehran University, which was concurrent with Iran’s period of political reform. The context of those days influenced all of us. There were also events in the region that impacted us, such as the Arab Spring, etc. During the Tunisian Revolution I travelled there and created some pieces about the events taking place in Tunisia and Egypt. My main subject matter was to make visible the violence that was taking place against the people.

Tavana _ Given the political irony of your work, are you worried about it being misinterpreted or misused? Especially given the prevalence of works that have a superficial layer of political protest in order to take advantage of a fad...

No, not at all. I believe pieces that have direct political references have an expiration date. But some events have such great political, social, and economic impact that they can be reinterpreted over and over again. I believe some works of art can also be reinterpreted along with these events.

Tavana _ Do you consider yourself a political artist?

Not at all. There is no such thing as a political artist. Politics is about creating change in effect and function, but art does not have a socio-political function. Political art is a tool used by governments as propaganda. Because of its aesthetic quality art is limited to an act of exhibition, which is in complete contradiction with function. An artist is a meddler, and he can have an impact through his work, commitment, and socio-political stance. Shajarian is an example of such an artist; with the issue surrounding his version of “Rabbana”. An artist needs the right context in order to intervene and have an effect.

Tavana _ Is it correct to say that the subject matter of your work shows a desire for a dialogue - especially with those in power? Every one of your series seems to be about a form of protest against political events (“Talqin” and “Xabt”), the law (“Children Program”), and social situations (“Zel”).

It is more a desire for protest rather than dialogue, a form of reaction to my context and society, not just in opposition to powers that be, but also attending to things in the area of art that I regularly have to deal with. I consciously choose subjects to see what happens when they get infected with the virus of art. What keeps me going is the awareness they create. For instance “Children Program” was about the execution of children under eighteen-years-old. Iran is among countries that have accepted item 37 of the Children’s Rights Convention, which is opposed to executing anyone under eighteen. Yet we end up executing children that commit crimes, after they reach legal age. I had an idea in mind with that exhibition. I had planned to get a number of well known and respected figures involved; to hand them the files of these convicted children, and ask them to attempt to gain forgiveness from the victims’ families (in order to stop the execution of the convicts). However after consulting with the children’s lawyers we ended up only having an exhibition, which didn’t receive much attention. This view (of social responsibility) has become more prevalent in my work.

Tavana _ All your series include references to violence and human pain, albeit in a metaphoric manner. But instead of creating a sense of empathy in the viewer, they create a desire for a form of reaction (at least this is the reaction I have to the work). How important do you find the viewer’s reaction?

Sometimes I begin a project be selecting a subject matter that can have a therapeutic effect on me. This is how it was with “Talqin”. Then at some point I decide to share the work with the viewer. It is here that I try to create a connection with the viewer through the use of layers and language as my medium. According to Marcel Duchamp, the two poles of the creation of art are the artist and the spectator. When I speak of making something “visible”, I am referring to the spectator’s gaze, which completes the work of art.

Mojtaba Amini | Xabt-E Aswa | 2014 | silk screen printing | 70 × 50 cm

Tavana _ One of the first things a spectator perceives in your work is language. Language, in particular Arabic, had a bold presence in your “Xabt” series and is an important aspect of your work. Why?

My interest is in the significance of language, not its form. In some pieces language becomes a medium. We (Farsi speakers) have certain things in common with Arabic. We can read Arabic and have Arabic texts in our traditional works of writing. The Qur’an is in Arabic. My father was familiar with the Arabic language and we had many Arabic books at home. Because of his old age and poor eyesight my father would often ask my siblings and I to read to him aloud, even though we wouldn’t understand the meaning of what we read. He would listen and correct us. But the main reason I use Arabic in my work is the broad meaning of Arabic words. For instance “Lahm” in Arabic means meat, human being, piercing the body, and lust. There are few words with such capacity in Farsi. This is the title I used for one of my pieces about violence. Or “Xabt-e Ašwa” means a camel that has a weak vision and can’t control itself when it walks; it alludes to the regime’s deviation from order. “Xabt” was the title of one of my series. It means to beat someone severely, to trample on someone or something, to strike someone with a sword, and the state of being nocturnally disoriented.

Tavana _ Another function of language in your work is the titles of the pieces. You make references to archaic meanings of Arabic words that sound familiar in Farsi, like what you explained about the “Xabt” series. Are you worried that the way you use language in the titles may create a distance with the viewer and act as an obstacle in his understanding of the work? Things become even more complicated in the English translation of the titles.

Marcel Duchamp believed a work’s title is an integral part of the piece of art, just like hues and forms. His work would have been lacking in meaning without titles; names like “Fountain”, or “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even” (La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, meme), also known as “The Large Glass”. I am always looking for ways to make things difficult for the viewer who likes things to be simple. I want to encourage him to reach a conclusion by putting together pieces of the puzzle. For the viewer who is interested in understanding my work there are items and signs that tie all my pieces together. For instance one of the pieces at “Talqin” exhibition at Aaran Gallery in 2012 was titled “Xabt-e Ašwa”. It was a metal frame ornamented with crystals. The frame was filled with camel wool. And my latest exhibition at Mohsen Gallery was called “Xabt”. This exhibition was in fact a complete explanation of that single piece (“Xabt-e Ašwa”) from Aaran Gallery. My primary audience is Farsi speakers, and all my work is initially exhibited in Iran. I am not concerned about the English translation of the titles, unless it becomes necessary. Some of the pieces include text in other languages. For instance in the “Talqin” exhibition I made six death masks whose titles were inspired by works by Käthe Kollwitz, which were carved in English on the frames. On another piece about Osip Mandelstam the Russian poet, I wrote “BEK”, which in Russian means century. It was a reference to Mandelstam’s famous poem, “My Century”.

Mojtaba Amini | Rahl | 2016 | wood, paper, animal glue, rope | 90 × 130 × 85 cm

Tavana _ Camel saddles (or Rahl, also related to the word Rahel) were an important part of that exhibition. The saddles look more like torture and execution devices, rather than a comfortable means of moving from one place to another. Perhaps this refers to the difficulty of the path, and the distressing situation of the points of departure and arrival. By de-familiarizing these objects and removing their functionality you created a visual experience that highlighted the concept of death.

That’s right. In Arabic Rahl means saddle and death. It is the root of the word Rahel, which means someone who has departed (both in terms of leaving one’s country, and in terms of passing away). “Rahel” was the title of one of the pieces in the “Xabt” series that referred to Syrian refugees drowning in the sea. It looked like a burnt black casket with a piece of skin moving back and forth inside, something like the motion of Syrian corpses on the surface of the sea. I used lead to write “al-aswad” (aswad means black), and what I meant was “almawt al-aswad” (Black Death), meaning a difficult death. It was a reference to a difficult death, by drowning in water, or by fire. Like you said, what I meant by movement and departure was a movement between life and death.

Mojtaba Amini | White Death, Death from Sickness | 2016 | wood, leather, lead, egg shell | 53 × 73 × 59 cm

Tavana _ The Arabic references in some of your pieces and titles are particularly successful. In addition to “almawt al-aswad” (Black Death – death by drowning) that you referred to above, there were two other pieces in the “Xabt” series titled, “almawt al-ahmar” (Red Death – horrific death), and “almawt al-asfar” (White Death – death by sickness). The first two are related to “Rahl” (departure). Why do you consider the third (“almawt al-asfar”) a violent death? In this piece you have included something that isn’t present in any of your other pieces: eggshells.

This piece is a small wooden table covered in leather. A lead plate is inserted into the table and two eggshells are placed on the plate. It is a reference to the death of Osip Mandelstam the Russian poet. Mandelstam was sent to a forced labor camp by Stalin’s orders, where he lost his life. At the time of Mandelstam’s arrest, Anna Akhmatova was a guest at his house. Mandelstam had borrowed an egg from a neighbor to make dinner for Akhmatova. She asked him to eat the egg before being taken away. In a way this act foretold his death in captivity. This is why I named the piece “almawt al-asfar”. Many have lost their lives like this in prison and captivity.

Tavana _ You had an installation at Mohsen Gallery titled “Majâ’a”. These were large ceramic vessels used for storing grain. Their emptiness and the fact that they were old implied the concept of hunger, pain, and death. It seemed like you were making a statement about the quality of people’s lives by eliminating them (the people) from the presentation. (You attend to this subject more seriously in the “Zel” series.) Are you attempting to show a sense of responsibility, or perhaps acting as a representative of your place of birth and childhood memories, with these types of projects?

The vessels were not ceramic; they were made of raw clay. Majâ’a means a year of famine in which many men and beasts die. I found some of these vessels in an abandoned village in Sabzevar. The village had been abandoned due to rural exodus, drought, and death. When I saw the empty vessels I was immediately reminded of death. I pulled them out of the rubble and brought them to Tehran. I later heard that in the past the vessels were sometimes used to carry a corpse. For instance if someone asked in his will to be buried elsewhere, they would put him in such a vessel, cover the top with clay, and move him to another location on camelback. So in a way this installation is also connected to camels and rahl (camel’s saddle).

To me this installation was also a depiction of violence; what we inflict on the natural world through incorrect policies. This is something we witness quite often nowadays, from unwanted relocation, to many other things that relate to the environment. The “Xabt” series was about all forms of violence and death. But my intention with this installation was not to make some sort of a responsible statement toward my place of birth - or out of any form of obligation. I have mentioned before that many of the material I work with come from where I was born; I know them well and am comfortable using them.

Mojtaba Amini | Maja’a | 2016 | jar, a container for grain and four

Tavana _ In different exhibitions at different times you have used chandeliers that are similar to one another. Does this element (made of burnt wood or other material) have a particular meaning to you?

I exhibited one of these chandeliers at Aaran Gallery, titled “Band”. It was made of identical pieces of charcoal that had been tied together. Band means the connection between two members or two joints; it also means confinement (imprisonment). It was a black mass hanging from ceiling to floor. Black dust would collect on the floor as the chandelier moved. That blackness is what I aimed for, which made sense in relation to the other pieces in the exhibition. I had taken light away from the chandelier and replaced it with blackness. I wanted to present blackness, referring to the bleak, hopeless situation of the time. I later saw many chandeliers made by artists in the past and present, with numerous examples in contemporary art. In western art there is a tradition where churches commission artists for chandeliers. I was interested in the difference between my chandelier and those commissioned by the church. The fact that mine was not commissioned automatically put it in contrast with its setting, and the use of black charcoal, and its contradiction with light, was another thing that set my chandelier apart from others I had seen.

Mojtaba Amini | "KhalghAviz" | Installation | Burnt wood, Rope, Iron, Lead | 150 × 150 × 90 cm | 2014

I later made two other chandeliers that were different from “Band”. They were inspired by the designs of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, the Italian artist famous for his etchings. Piranesi has a series of famous etchings depicting empty, dark, prisons with winding staircases, and figures being tortured. Some of these images include chandelier-like objects used for torture. I wanted to tie my chandeliers to Piranesi’s designs, in order to include his concepts into mine. I named one of the chandeliers “Khalgh-aviz”. This piece was also made of charcoal and burnt wood, and its form was a combination of several Eslimi patterns. The chandelier did not emit any light. There was a rope hanging from the chandelier and each time you pulled on it, a piece of charcoal would detach from the chandelier and fall to the ground, similar to how a guillotine functions. It also included a piece of lead, which made it heavy. The lead was a reference to the material used for making bullets. In another piece I made a metal case, similar to a torture device used in the medieval period, where a person would be placed inside a tight box where he would die from exhaustion. I hung a number of skin churns inside the case and titled the work “Jeld” (Skin). In Arabic Jeld can be used to indicate both human and animal skin. The churns I used were made of goatskin, which added an extra layer of violence to the work.

Tavana _ In addition to Tunisia you also had an installation in Seoul. What was the subject of that piece?

During my stay at Seoul I was struck by a series of identical sculptures throughout the city. They depicted a barefoot girl sitting on a chair, with an empty chair next to her. These pieces referred to Korean “comfort women”. During World War Two the Japanese kidnapped around two hundred thousand Korean women and used them as sex slaves for Japanese soldiers. Korean activists continue to protest against this, asking for a formal apology from the government of Japan. Japan has yet to accept responsibility for this act and refuses to apologize. This subject became a source of inspiration for me. I connected two traditional Korean dinner tables together and made something like a bed. I covered it with a thin layer of white soap that ended up looking like human skin. Over this I hung a portrait of a surviving “comfort woman” sitting on a bed holding a dog in her arms. I titled the piece “Death is the highest orgasm”, and included a few designs and collages in the exhibition.

Tavana _ Because of your focus on the issue of death this absence exists in all your pieces, and not just the one about the “comfort women”. But the absence does not apply to you yourself. You are directly present in the “Talqin” series.

The direct presence of the body in that series was completely palpable to the viewer. But it was different for me, because I got to observe the wasting away of the body and visualize its absence. This project formed the basis of all that came afterwards.

Mojtaba Amini | Untitled | 2017 | Mixed Media | 85 × 115 cm

Tavana _ Your projects from different periods are related to camels in different ways. You mentioned the connection between camels and death. Through its different body parts and the significance of each part, the animal’s presence is felt in your work without it actually being seen. It is mainly manifested in material and language. But it seems in your mind camels are more important than this. I would like you to speak some more about this.

No, it is nothing beyond what I include in the work. I decided to use camel oil to make the “Talqin” sculpture, and during my research in Arabic culture and language, I kept running into the concept of camels. This animal has a particular significance in Arab culture, and there are many words in the Arabic dictionary related to camels. Its primary significance is in relation to death, and in calculating the amount of diyeh (blood money) payable to the deceased. Even today camels are the benchmark for the calculation of blood money.

Tavana _ Concepts and ideas are what lead to your final product, defining its language and media. Given the variety in the appearance of your work, I am interested in learning about your process of transforming concepts and ideas into a visual language.

I often make sketches, which gradually change shape. Words and sentences get added on. I cut up several sketches and make something new by gluing them together. I begin each piece by putting together writings and drawings. The work starts with a single word or title, which manifests itself in a design that may change shape and form. Sometimes the word or sentence itself ends up being the final product, like in the case of “Sabr-ol-Jamil”, where lead and charcoal are placed side-by-side.

Tavana _ Was the material also important in your choice of media? What I am trying to get at is the extent your choice of material has led you away from painting as a medium?

I studied painting at the university. But I began work as an artist by making sculptures and don’t consider myself a painter. Recently I have tried to get back to painting by making collages. Creating sculptures out of traditional sculpting material and ready-to-use items is easy. I want to make it hard on myself and return to painting.

Tavana _ A tangible aspect of your work is the material’s physicality, I mean the physical work that goes into its creation. This process and the time you put into it, creates an opportunity for greater scrutiny.

These creations are rooted in my past experiences. During my student years I had an advertising company where I used to make metal trophies and sculptures. Later I began building moveable advertisements for billboards. I have also started to do carpentry, and I bring all these physical experiences into my artwork. These experiences are how I become familiar with material.

Tavana _ In that performance your body’s endurance and reaction became part of the piece, and was something you could not anticipate. How long did the performance last, and what ended up happening to your body?

I wasn’t trying to display my body’s endurance. These types of performances where the artist uses his body as material for the work and puts it through a difficult situation require practice and experience. This was the first performance piece I had done. I didn’t have the capacity to bear the sensation of burning and the resulting blisters. I covered my body in a cool, moisturizing material prior to the performance in order to reduce the effects of burning, kind of like I was preparing for a theatrical show. I was curious to see if the viewers would get involved or not. And none of them did! It took less than two hours and resulted in a few blisters.

Tavana _ It is difficult to compare your performance with the self-immolation of the Tunisian worker in terms of viewer interference. In a performance atmosphere, given the chandelier and your tattooed body, there is a meaningful distance between the artist and the observer. But the moment of Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation must have been quite strange and unfathomable.

That’s exactly right. The viewers knew they were witnessing a performance. It was a symbolic act about the Tunisian Revolution, and how a street vendor challenged the power of Ben Ali, the Tunisian dictator. I had intended to perform the piece in front of Ben Ali’s place of residence, but it wasn’t approved. I ultimately performed it in front of a villa in the Seyyedi Bou-Saeed district that belonged to one of his relatives.

Tavana _ The Arabic language and the special political situation of Arab countries (I am referring to the Arab Spring) are very important in your work. Do you also follow the visual arts and culture of these countries?

I am in touch with some Tunisian artists. I also follow other Arab artists through artistic events in the region. But I follow Arabic music more than anything else.

Tavana _ Do you follow works of Arab and other international artists that are similar to your own?

I do so less and less. I continue to try to see as much work as I can. I try to get my eyes used to seeing good art, particularly painting and photography.

Tavana _ This points to your recent preoccupation with painting. It may be too soon to speak of a return to painting at this point, although your sketches and collages show you were never entirely detached from it. But if we put your early work in the area of visual arts, which were caricatures, next to your most recent projects, the path you’ve gone through is quite curious.

As I mentioned before, I was drawn toward making sculptures because of other activities I was involved in, which led me away from painting.

Tavana _ The exhibition of conceptual art at Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMOCA), which later continued under the title of new art, took place when you were a student. Is that correct?

Yes, I was in my third or fourth semester.

Tavana _ It was probably too early for it to have left a direct impact on your work, but did it influence your view in any way? Were your friends and classmates influenced by this exhibition?

No. I saw that exhibition several times and found it quite interesting. But that’s about it.

Tavana _ The more questions I ask about elements that influence your work the clearer it becomes that you are more interested in subjects beyond the world of art; things like violence, politics, religion, etc. Contemporary life, particularly in recent years, abounds with such concepts. How does Mojtaba Amini experience such a world?

I agree with Murakami where he says, “The world is becoming a better place”; even though we live in an unstable area in the world, and despite the fact that fundamental questions remain unanswered and nothing significant has really changed. Art is not everything. We use it to scream out as citizens, to express our beliefs, to protest, and to build a better place. Each person tries to achieve this in a different manner.

Tavana _ This optimistic point of view has a paradoxical relationship to the bitter expression present in your work; pieces about death and violence depicted in a terrifying language.

Our lives are full of contradictions and enigmas.

Tavana _ In your last exhibition “Zel” (Shadow) you display a paradox between a turquoise and a miner.

“Zel” is the story of a turquoise miner from Neyshabur. In the past I mingled with people who had strange lives. I was interested in finding a way to narrate their lives, and I tried writing about them several times, but failed each time. So instead, I decided to use a method I was familiar with. I went to a turquoise mine in Neyshabur this year and asked about my mother’s uncle. In fact I was asking about a miner who spent a lifetime in the darkness of the mines. “Zel” is the story of his life and death in the dark tunnels of the mine; a contrast between his poverty and the turquoise gem used in making jewelry.

Tavana _ You extend the cavity and dark void of the mine into the worker’s life. Mine workers never benefit from the gems they find.

Cavities, or dark voids as you call them, are what I focused on in this narrative. I also compared the dark hollows of mines to prison cells and graves, as well as the mineworker’s body cavities, and the ring setting where a gem is placed. The reference to prison cells was because all the openings into a mine are guarded with heavy iron doors and bars. Just like a prison, the doors are sealed shut when the workers enter and exit the mine. There are also guards that are constantly on watch and sometimes search the workers’ body cavities. The reference to graves came from the fact that the miners seem to bury themselves in graves they themselves have dug. The piece was about the scent of explosives, the exhausting work of chipping away at stone, all of it.

Tavana _ The worker in this series is a symbol of a greater society (not necessarily the working class) that forgets itself (is forced into forgetting itself), and whose life turns into a slow death. In this series too death and the absence of the body take center stage, and not just the death and body of the person you used as an excuse for the project.

I used that person to express and make visible part of the problems faced by workers, their pain and suffering which we hear about more and more. This is clear in “Forud” (Descent), although it uses the absent body of a worker to refer to a social body of workers.

Tavana _ The word “Rezghi” can be seen on some of the collages, along with others that are sometimes legible and sometimes not, like Deh-e Bala (upper village), Gol-Andam, Muezzin (one who recites the call to prayer), Mandelstam, Manāqeb va Masaēb-e Zendan (pros and cons of prison), Ādat Kardan (getting used to), etc. The words look as if they’ve been written on the collages in a frantic, feverish manner. Is it important if the viewers read these or not?

Not necessarily. These collages are depictions of events, and sometimes end up looking like drawings. I write words or glue newspaper cutouts over them. Each word will remind the viewer of present or past events, or something that has a connection to the other pieces. The collages are empty boxes that act as reminders of events or certain deaths, and they are directly related to the photographs showing the workers washing their bodies.

Tavana _ The layering of paper and cardboard, the repetition of writing, the physical act of doing things like covering the work in soot, and the additions and deletions from the collages in general, seem like ways of creating more time to think and scrutinize during the process of creation. Perhaps the series is a form of therapy for you.

That may be true. Using recycled paper and glue can help the creative process. Like pen and paper they are handy material and easy to use.

Tavana _ Do you mean that in addition to the installation, you have also used Azin Haghighi’s photographs in the collages?

Yes, I used them both in the collages and as photographs that I manipulated in order to present another interpretation of them.

Tavana _ The experience of witnessing miners’ struggles up close has led you to express the fundamental problems they face, things that an outside observer may never witness. I believe these issues appear both in the subject matter, as well as in the material used in the work. It is as if during the process of learning (research), you gained certain experiences, and the work is ultimately a means of sharing these experiences with the viewer.

My only experience was spending some time in the turquoise mine in Neyshabur. It was just a passing observation of the mineworkers’ situation and cannot be considered a true understanding of the hardships they face. This is why I turned to a photographer who has spent years with miners, has lived with them, and has a deeper understanding of their conditions. My experience of being in the mine has a close connection to the subject of the work as I mentioned before. I brought along some unrefined turquoise stones from the mine in Neyshabur. At first I intended to build a wall with them, representing a wall that mineworkers spend hours extracting turquoise from. In the end I placed all those pieces of stone on a ring setting. I made a ring that is possible to make, but impossible to wear because of its immense weight.

Mojtaba Amini | 1371-1391 | 2018 | collage | 57 × 78 cm

Tavana _ Once again it refers to the paradox of the beauty and value of turquoise in contrast to the mineworkers’ lives. Large unrefined pieces of stone that ultimately contradict the beauty and functionality of a ring. But what I was referring to is your persistent interaction and entanglement with the subject matter. You go to the mine, you buy turquoise stones, you have them carved, you visit a worker’s house that becomes an excuse for the entire series... Don’t you consider this sufficient for finding a metaphoric language and deep subject matter?

It is true that since everything does not take place inside the studio I get closer to the subject matter in a variety of ways. Someone asked me if I could have used other pieces of stone instead of bringing so many all the way from Neyshabur. But it was through these comings and goings that I got to get close to the mineworkers and learn more about them. And it was important for me to use stone from the place these workers had spent centuries, carving 6,000 kilometers inside the mountain. I wanted my material to be the output of their many hours of pain and suffering.

Tavana _ More than any of your other exhibitions, “Zel” is about a narrative. Through every single piece you try to get the viewer to experience the lives of turquoise mineworkers. The collages play a significant role in this series. The political act has become more social. Even though the series can be seen as a continuation of your previous work, nonetheless it seems to have opened up a new chapter in your artistic life.

It is true that the narrative aspect of this series (the story’s main character and the narration of his life and that of his social class) sets this exhibition apart from the others. I will continue this act of storytelling to narrate the lives of people close to me. The story of this particular worker begins from a dark, dyeing workshop, where he turns his hands and threadbare coat black. From that black workshop he enters the dark hollow of the mine. The story ends with the worker’s blackened uniform, a few pieces of turquoise, and his death.

Tavana _ You mentioned before that the desire to narrate these people’s lives tempted you to write about them. Can we speak a bit about literature and authors you admire? What sorts of books do you read most often, and who are the people you turn to in order to develop your ideas and concepts?

I have read Russian literature and history more than others, but I turn to different books and authors. Recently I’ve been reading interviews and international novels. I look at different authors and books depending on the concepts or ideas I am involved with. I look for inspiration in many different places. I surf the Internet regularly, and photographs have a great impact on my work. Discussions with my friends also help me develop my ideas.

Tavana _ You speak often about your ideas for future work. I have seen many drawings and sketches in your studio. You spend the entire day working, but to an outside observer it may seem as if you don’t have a high output. Maybe you spend a lot of time thinking and experiencing, or maybe you are just a slow worker. Or perhaps you are a perfectionist. Which is it?

I believe in working a lot, but not in producing a lot. I admire the Croatian artist Mladen Stilinović and his thesis on laziness. One of his most famous pieces depicts the artist taking a nap and is titled, “Artist at Work”. A great part of my day is spent making drawings and sketches. I make sketches anywhere I am, and use whatever surface is handy. I find artists’ sketches and drawings more interesting than the final pieces they exhibit. When I visit my friends’ studios I am constantly looking at the walls, making sure I don’t miss any interesting drawings. There are few artists in Iran who use pen and paper as their medium. Everything they do seems to be intended for an exhibition. In the west painters sometimes make sculptures, and sculptors and filmmakers make drawings and etchings. Every medium is used in order to develop an idea. But here the artist’s creative process is missing. Everything is reduced to the final exhibited piece, which does not allow the work to be understood completely. This is because of our incorrect education system.

Tavana _ There are different components involved in understanding the various, complicated aspects of an artist’s work, some of which may be entirely unrelated to the final product. Do you think there is any attention paid to this issue in Iran’s contemporary art scene? Do you think artists, universities, gallerists, curators, critics, etc. are concerned about these details (components) that I find quite critical?

We have rapidly moved into the economic realm of art, and such components have no place in this realm. A while back I read something by a teacher/critic where he claimed that art institutions had to carry the weight of education in lieu of universities. He was referring to the type of institutions that charge a ton of money for a few art classes. Perhaps in a place run by artists it wouldn’t be like that.

Does your optimism about the world also apply to Iran’s visual art scene?

The new generation will make the situation better. They have a better understanding. The new generation takes underpasses and street barriers at Vali Asr intersection as its subject matter. My generation wants to know why whales commit mass suicide.